1.060.447

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

VISSZA

A TETEJÉRE

JAVASLATOKÉszre-

vételek

The Third Man of the Double Helix

| Kiadó: | Oxford University Press |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | Oxford |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Ragasztott kemény papírkötés |

| Oldalszám: | 274 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | |

| Kötetszám: | |

| Nyelv: | Angol |

| Méret: | 24 cm x 16 cm |

| ISBN: | 0-19-860665-6 |

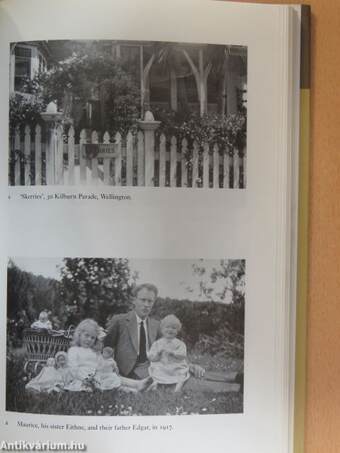

| Megjegyzés: | Fekete-fehér fotókkal. |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

Fülszöveg

Francis Crick and Jim Watson are well known for their discovery of the structure of DNA in Cambridge in 195 3. But they shared the Nobel Prize for their discovery of the Double Helix with a third man, Maurice Wilkins, a diffident physicist who did not enjoy the limelight. He and his team at King's College London had painstakingly measured the angles, bonds, and orientations of the DNA structure - data that inspired Crick and Watson's celebrated model -and they then spent many years demonstrating that Crick and Watson were right before the Prize was awarded in 1962. Wilkins's career had already embraced another momentous and highly controversial scientific achievement — he had worked during World War II on the atomic bomb project — and he was to face a new controversy in the 1970s when his coworker at King's, the late Rosalind Franklin, was proclaimed the unsung heroine of the DNA story, and he was accused of exploiting her work.

Now aged 86, Maurice Wilkins marks the fiftieth... Tovább

Fülszöveg

Francis Crick and Jim Watson are well known for their discovery of the structure of DNA in Cambridge in 195 3. But they shared the Nobel Prize for their discovery of the Double Helix with a third man, Maurice Wilkins, a diffident physicist who did not enjoy the limelight. He and his team at King's College London had painstakingly measured the angles, bonds, and orientations of the DNA structure - data that inspired Crick and Watson's celebrated model -and they then spent many years demonstrating that Crick and Watson were right before the Prize was awarded in 1962. Wilkins's career had already embraced another momentous and highly controversial scientific achievement — he had worked during World War II on the atomic bomb project — and he was to face a new controversy in the 1970s when his coworker at King's, the late Rosalind Franklin, was proclaimed the unsung heroine of the DNA story, and he was accused of exploiting her work.

Now aged 86, Maurice Wilkins marks the fiftieth anniversary of the discovery of the Double Helix by telling, for the first time, his own story of the discovery of the DNA structure and his relationship with Rosalind Franklin. He also describes a life and career spanning many continents, from his idyllic early childhood in New Zealand via the Birmingham suburbs to Cambridge, Berkeley, and London, and recalls his encounters with distinguished scientists including Arthur Eddington, Niels Bohr, and J. D. Bernai. He also reflects on the role of scientists in a world still coping with the Bomb and facing the implications of the gene revolution, and considers, in this intimate history, the successes, problems, and politics of nearly a century of science.

Maurice Wilkins was born at Pongoroa, New Zealand, in 1916. He studied physics at Cambridge, graduating in 1938, and went on to work in J. T. (later Sir John) Randall's research group at Birmingham. In 1944 he moved to Berkeley, California, to work on the Manhattan Project. After the war he joined Randall's new biophysics group at St Andrews. The group moved in 1946 to King's College London and it was here where Wilkins began X-ray diffraction studies of DNA. These X-ray measurements, made with Rosalind Franklin and others, eventually established the correctness of the double helix structure of DNA proposed in 1953 by Watson and Crick at the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge. In 1962, Crick, Watson, and Wilkins were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for this I

discovery.

Emeritus Professor of Biophysics at King's College London, Maurice Wilkins lives in London with his wife Pat.

Vissza

Témakörök

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Szépirodalom > Regény, novella, elbeszélés

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Természettudományok > Biológia

- Szépirodalom > Regény, novella, elbeszélés > Az író származása szerint > Európa > Nagy-Britannia

- Természettudomány > Biológia > Biológia, általános > Genetika

- Természettudomány > Biológia > Biológia, általános > Tudósok

- Természettudomány > Biológia > Biológia, általános > Idegennyelvű

- Szépirodalom > Regény, novella, elbeszélés > Tartalom szerint > Életrajzi regények > Önéletrajzok, naplók, memoárok