1.069.667

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

VISSZA

A TETEJÉRE

JAVASLATOKÉszre-

vételek

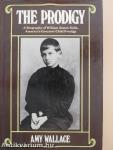

The Prodigy

A Biography of William James Sidis, America's Greatest Child Prodigy

| Kiadó: | E. P. Dutton |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | New York |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Félvászon |

| Oldalszám: | 297 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | |

| Kötetszám: | |

| Nyelv: | Angol |

| Méret: | 24 cm x 16 cm |

| ISBN: | 0-525-24404-2 |

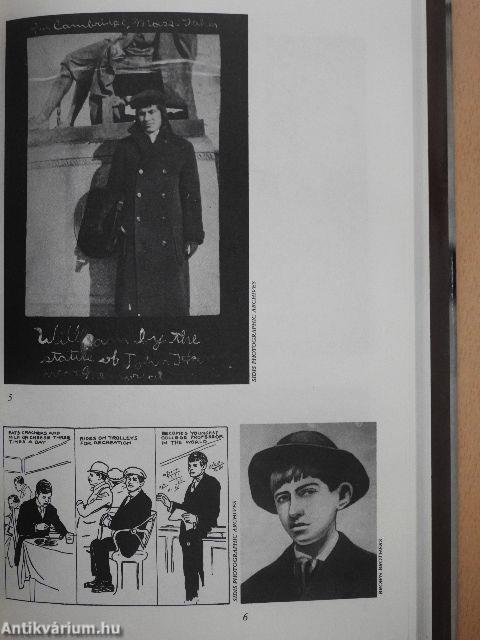

| Megjegyzés: | Fekete-fehér fotókkal, illusztrációkkal. |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

Előszó

TovábbFülszöveg

THEPROMGY

AMY WALLACE

In 1910, the words "child prodigy" meant one thing to most Americans: twelve-year-old William James Sidis. His IQ was an estimated 50 to 100 points higher than Einstein's, the highest ever recorded or estimated. His father, a pioneer in the field of abnormaJ psychology, believed that he and his wife could create a genius in the cradle. They hung adphabet blocks over the baby's crib— aind within six months little Billy was speaking. At three, he was typing and had taught himself Latin. At five, he wrote a treatise on anatomy, and, by aige six, he spoke a't least seven languaiges fluently.

By the time William entered Hau^aird at eleven, he was also a mathematical prodigy. He stunned the nation with his lecture on Four-Dimensional Bodies, and articles about him appeaured on the front pages of the country's leading newspapers. By the time he graduated from Harvard at sixteen, he was desperate for privacy. He told the press: "The only way to live the perfect... Tovább

Fülszöveg

THEPROMGY

AMY WALLACE

In 1910, the words "child prodigy" meant one thing to most Americans: twelve-year-old William James Sidis. His IQ was an estimated 50 to 100 points higher than Einstein's, the highest ever recorded or estimated. His father, a pioneer in the field of abnormaJ psychology, believed that he and his wife could create a genius in the cradle. They hung adphabet blocks over the baby's crib— aind within six months little Billy was speaking. At three, he was typing and had taught himself Latin. At five, he wrote a treatise on anatomy, and, by aige six, he spoke a't least seven languaiges fluently.

By the time William entered Hau^aird at eleven, he was also a mathematical prodigy. He stunned the nation with his lecture on Four-Dimensional Bodies, and articles about him appeaured on the front pages of the country's leading newspapers. By the time he graduated from Harvard at sixteen, he was desperate for privacy. He told the press: "The only way to live the perfect life is to live it in seclusion,"

William's dramatic rebellion against his parents, against academia, and against the world's expectations led him

(continued on bAck ilAp)

(continued from front flp)

first to a jail cell and a scandalous tried, aind then to one menizd job after another, where he hid the secret of his genius while he produced book after book under false names: books on cosmogeny, American history, radical libertarian politics, and his eccentric hobby, the collecting of streetcair transfers.

Today, the nzime William James Sidis means one thing to a handful of educators: a burned-out failure who died, ironically, of a cerebral hemorrhage, the victim of Svengali parents and a high IQ. Now, in the era of "superbabies" and the "quest for excellence," forty yeATS after his death, the possibility of William's—and his parents'—failure is more relevant tham ever. In The Prodigy Amy Wallace, one of our most engaging writers on the subject of the sometimes bizarre, always enthradling, breadth aind variety of the human experience, explodes the myth of Williamtv James Sidis's fadlure and investigates and reveads his unique success.

AMY WALLACE is coauthor of The Book of Lists, The Psychic Healing Book, and The Two (a biography of the original Siamese twins), among others. She her husband live in Berkeley, California. Vissza

Témakörök

- Életrajz > Történelmi személyiségek > Külföldi

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Művelődéstörténet

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Pedagógia

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Életrajz > Történelmi személyiségek > Külföldi

- Művelődéstörténet > Kultúra > Története

- Pedagógia > Egyéb