1.068.031

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

VISSZA

A TETEJÉRE

JAVASLATOKÉszre-

vételek

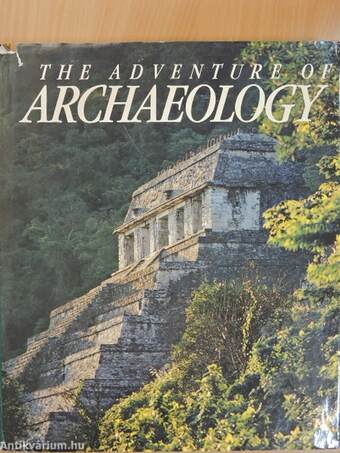

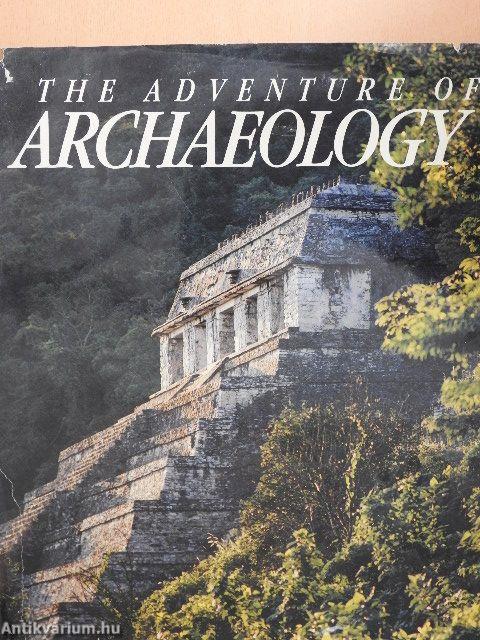

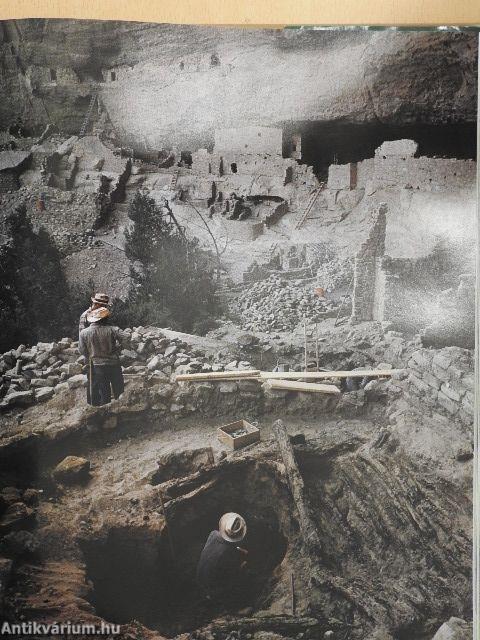

The Adventure of Archaeology

A régészet kalandja

| Kiadó: | National Geographic Society |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | Washington |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Vászon |

| Oldalszám: | 368 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | |

| Kötetszám: | |

| Nyelv: | Angol |

| Méret: | 28 cm x 24 cm |

| ISBN: | |

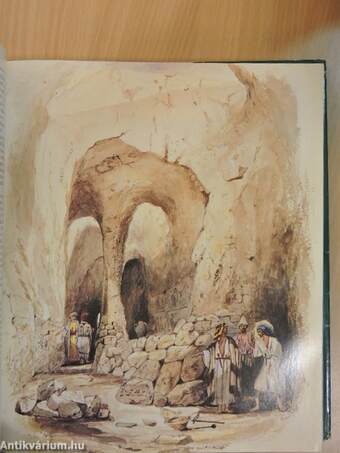

| Megjegyzés: | További grafikus a kötetben. Színes fotókkal, illusztrációkkal. |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

Előszó

FOREWORD i /n the beginning____" These words open the Scripture that is sacred to a fourth of the world's people. But they reflect an abiding curiosity that is shared by humán cultures everywhere-a... TovábbElőszó

FOREWORD i /n the beginning____" These words open the Scripture that is sacred to a fourth of the world's people. But they reflect an abiding curiosity that is shared by humán cultures everywhere-a thirst for knowledge about our past. Every society has speculated about its origins. And many have dug into the earth in search of hard evidence. One 18th-century British cleric shoveled into 31 ancient burial mounds in a single day. Today it can take weeks to uncover just a few square feet of an ancient city mound, and months more to preserve and study the finds. Digging up the past has become a sophisticated science that draws on experts in dozens of specialties. TheAdventure of Archaeology telis the story of how that science came into being-a compelling tale of tourists and treasure hunters, of strong-minded adventurers, of patient excavators laboring alone, of teams of scholars trekking into the desert or diving into the deep. In these pages you will witness the discovery of forgottén civilizations-the Assyrians and Sumerians of Mesopotamia, the Minoans of Crete, the Harappans of the Indus Valley, the Olmec of Mexico. In words and images you will travel through time with the Leakey family to the earliest chapters of humán existence in East Africa, and with Kathleen Kenyon to Jericho's 10,000- year-old walls. You will look over the shoulder of Howard Carter as he opens Tutankhamun's tomb, and dive with George Bass as he studies a Bronzé Age shipwreck on the bottom of the Mediterranean. Our journey alsó takes you to laboratories to witness the development of radiocarbon dating, to peer into a microscope at fossil pollen, and to discover what stone tools and bits of bone can teli us about the past. A fragment of pottery may reveal nearly as much as an entire bowl, A single coin in the proper context can yield more useful information than a golden trove ripped from the ground. Each clue, however small, adds to our knowledge of how our ancestors lived. A century and a half ago, scholars assumed that humans had appeared on earth only six thousand years before and that the ancient Egyptians had created the first civilization. Today archaeologists study almost two millión years of humán existence and dozens of early civilizations, known to us from thousands of sites, large and small, on coastlines and i mountaintops, in deserts and rain forests, deep below city streets, and even on the bottoms of rivers, lakes, and seas. Unfortunately the triumph of archaeology lies in the shadow of tragedy. As archaeologists labor to record time's irreplaceable archives, eager collectors continue to buy anything they can for their own pleasure or profit. Housing developments, farms, factories, highways-these and more are obliterating archaeological sites every day. The Parthenon in Athens is crumbling, partly because of air pollution; Kampuchea's temples at Angkor were caught in the cross fire of war. The future of the past lies in our hands, a precious legacy to pass on to our descendants. But so much has been destroyed that, if we are not careful, there will be no past to leave them. One day not long ago I visited the ancient beach at Herculaneum (opposite), a seaside Román city buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in a.d. 79. Beside me was Sara Bisel, a noted physical anthropologist. And before us lay the skeletons of Román citizens who had died in the tragedy, fragile relics preserved for centuries in the mud. More skeletons would soon be unearthed-and, if not protected, would begin to deteriorate in the light and air. The National Geographic Society had provided emergency funding to send Dr. Bisel to Italy for the painstaking task of preserving and reconstructing the skeletons. Nearly 140 have been excavated thus far, and somé experts say that hundreds, even thousands, more may await discover)' on Üie buried beach. For the first time, modern science will study humán remains from the days of ancient Rome. Occupations, diseases, diet, appearance-the dead will teli many tales about life in Román times. And the National Geographic will continue, as it has for nearly a century, to support such research in every corner of the world. I sincerely hope that you will enjoy this true-to-life adventure story. If it shows you that archaeology is a science and not a treasure hunt, then it has helped ensure a future for our common heritage-the humán past. Presidenl, National Geographic Society VisszaTartalom

FOREWORD6

THE ADVENTURE BEGINS 9

THE TREASURE HUNTERS 29

IN SEARCH OFBURIED CITIES 57

FROM SPORT TO SCIENCE 87

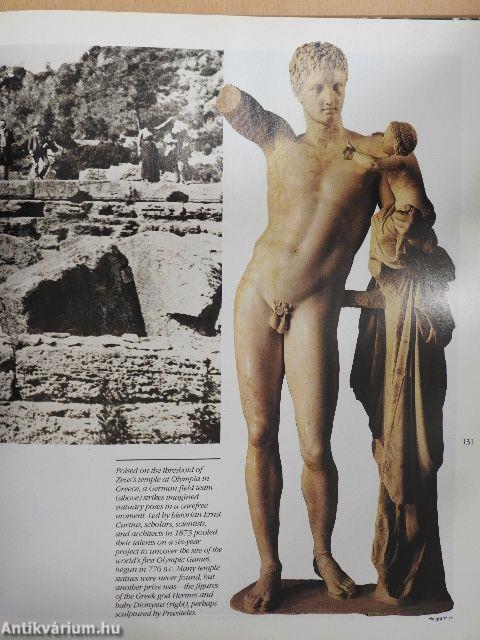

TOMBS, TEXTS, AND TROPHIES 105

SEEKING THE FIRST AMERICANS 133

PUTTING TIME IN ORDER 159

A NEWLOOKAT THE NEW WORLD 187

SCIENTISTS IN THE FIELD 215

WHEN, WHERE-AND WHY 243

LOST SHIPS, SUNKEN CITIES 271

TO THE ENDS OF EARTH AND TIME 297

THE FUTURE OF THE PAST 327

ADVENTURERS AND ARCHAEOLOGISTS: Three Centuries of Discovery 356

JOURNEY THROUGH THE AGES: A Calendar of World Cultures 358

BIBLIOGRAPHY 360

AUTHORS BIOGRAPHY/ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 361

ILLUSTRATIONS CREDITS 362

THE PAST ON DISPLAY 363

WHERE TO GO ON DIGS 364

INDEX 364