1.067.694

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

VISSZA

A TETEJÉRE

JAVASLATOKÉszre-

vételek

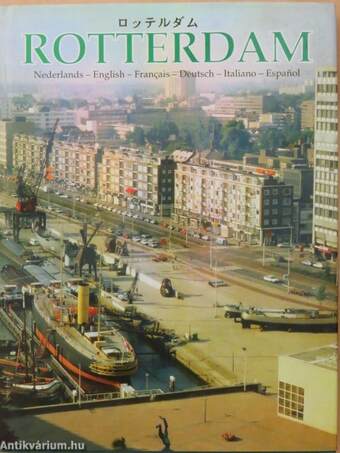

Rotterdam

Nederlands - English - Francais - Deutsch - Italiano - Espanol

| Kiadó: | Illustra |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | Rotterdam |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Fűzött keménykötés |

| Oldalszám: | 102 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | |

| Kötetszám: | |

| Nyelv: | Holland Angol Francia Német Olasz Spanyol Japán |

| Méret: | 27 cm x 20 cm |

| ISBN: | 90-6618-582-1 |

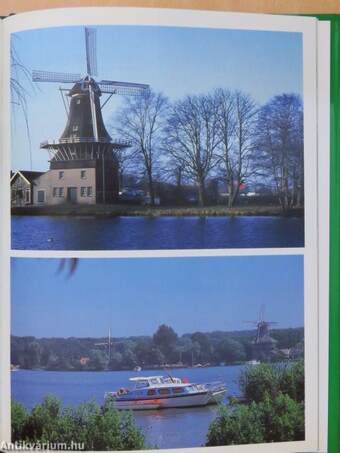

| Megjegyzés: | Színes fotókkal, térképekkel. |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

Előszó

8 Rotterdam: city of the Meuse and the Rhine

Rotterdam has always been first and foremost a harbour. It started as a fishing harbour which was so favourably situated in the bend in the Rotte,... Tovább

Előszó

8 Rotterdam: city of the Meuse and the Rhine

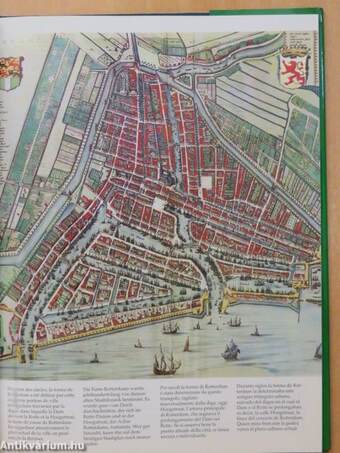

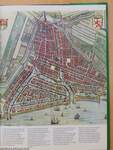

Rotterdam has always been first and foremost a harbour. It started as a fishing harbour which was so favourably situated in the bend in the Rotte, kept clean by the ebb and high tides, near the dam which connected the Westzeedijk and the Oostzeedijk. Rotterdam grew to become a trade and "Sea Beggars'" harbour and finally developed into a world harbour. A wide diversity of products from all comers of the world are imported, transshipped and forwarded in the harbour or processed locally. The actual city of Rotterdam was a triangle situated roughly between the present Oostplein, Hofplein and the Willemskade, and this continued to be the characteristic shape of the city until the days of the French. More and more people had to be housed within the city walls and their ten gateways, as the flourishing harbour called for ever increasing numbers of hands. The workers were packed in like sardines in a tin. Wherever there was room left, a row of houses would be planted, often back to back with another row. Open space, light and air were sparse and the sanitary facilities in particularly were not calculated to cope with the number of people involved. This wasn't without results. Halfway through the nineteenth century, the city was stricken by cholera epidemics which claimed many a victim. Shocked by this catastrophe, or maybe the churchyard in Crooswijk was getting overfull, a closed sewerage system was built in 1866. The "Mannheim" Act of 1868 freed the international Rhine navigational route for all nations, goods and persons. This signified the end of an age old system of tolls and restrictions, the hinterland became freely accessible as from that moment. The sea became more accessible in 1871 upon completion of the Nieuwe Waterweg. Expansion of the city then became absolutely inevitable as the population continued to grow. The inward flow of all those people led to Rotterdam outgrowing itself. The city expanded and even dared to take the plunge across the river to the South. Up until that time, the only things built in the Feijenoord area had been the Admiralty's gallows and a plague house, which was only actually used as a prison for English soldiers and a workhouse for paupers. There were plans to build houses in Feijenoord in 1834 though they weren't realised until some thirty years later. By this time, Feijenoord and Katendrecht had been annexed to Rotterdam and the local council had received an offer from the Rotterdam Trade Association to build harbours in concession. The offer was eagerly accepted and the local council agreed to build the Willemsbrug in return. Before the end of the nineteenth century, the Rijnhaven had been completed on the left bank of the Maas, followed by the Maashaven in this century. Prior to the first world war, constructions were begun for the Waalhaven, which was finally completed in 1931 and which was the world's largest bulk cargo harbour for quite some years to come. Rotterdam harbour began to break the world records. Harbour expansion on the right bank was not overlooked. The city of Rotterdam also blossomed in the periods between the two world wars, or to be precise, in the two periods directly following the first world war and likewise, following the second world war. The first period saw lots of work being carried out on city sanitation, and the infamous Zandstraat area, once the centre of the red light district, had to make room for the City Hall constructions. The pivoting bridge was replaced by the "Hef" (lifting bridge), which became the subject of Joris Ivens' famous film in 1928. Obviously, the economic crisis took its toll on Rotterdam harbour and its activities, though the construction of the Nieuw-Amsterdam by the Rotterdam Dry Dock Company as an employment project certainly appealed to the imagination of the city. By the time it was put into service in 1938, the worst of the crisis seemed to have passed. Rotterdam had also begun on the construction of the Maas tunnel, which was the first Dutch tunnel, and the new Exchange building stood proudly in its scaffolding on the Coolsingel. It was still in the scaffolding when the entire historical inner city went up in flames on the 14th

May, 1940. This is not the time or place to give a complete account of what was lost, suffice to say that it was a miracle that while 78,000 Rotterdam people lost their houses, there were but 900 dead. These numbers were to increase as the Second World War continued, as Rotterdam was not spared from the allied bombing raids.

On the 22nd September 1944, the occupying forces began to systematically destroy the harbour works and for ten days the entire city rumbled in its foundations. In the tormented city, the infuriated Rotterdam people ground their fists helplessly in their pockets, waiting, surviving a winter starvation before they could get back to work following the liberation of May 5th, 1945. In the post war years, the city became well aware of the crisis of the thirties and the dangers of such dependence on transit goods. Industry had to be brought into the area. Large scale plans were made, looking well into the future and the Botlek area was constructed. Expectations were that this would provide solace for the industries until into the eighties but the Botlek was full by 1960: Rotterdam had clearly underestimated its own attraction. In 1957 a new phase in the expansion plans for the harbour was heralded: Europoort (Gateway to Europe). A name which denotes exactly what was required, but which was actually out of date by 1963. In that year, Rotterdam was named as the world's largest harbour for the first time in history. A title which is still proudly carried: the world's largest goods harbour. The harbour has outgrown the city of Rotterdam, both literally and figuratively because it's simply not possible to extend it further than the North Sea and the Maas estuary. Vissza

Témakörök

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Többnyelvű könyvek

- Útikönyvek > Európa > Nyugat-Európa > Városai

- Útikönyvek > Idegennyelvű útikönyvek > Egyéb

- Útikönyvek > Utazás, turizmus

- Útikönyvek > Természetjárás, túrák > Városnézés

- Művészetek > Fotóművészet > Albumok > Tematikus

- Művészetek > Fotóművészet > Idegen nyelv > Többnyelvű

- Művészetek > Fotóművészet > Témái > Városok > Külföldi