1.067.285

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

VISSZA

A TETEJÉRE

JAVASLATOKÉszre-

vételek

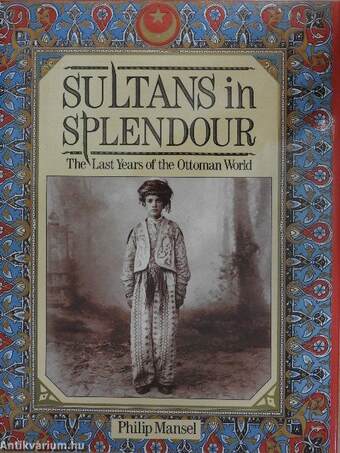

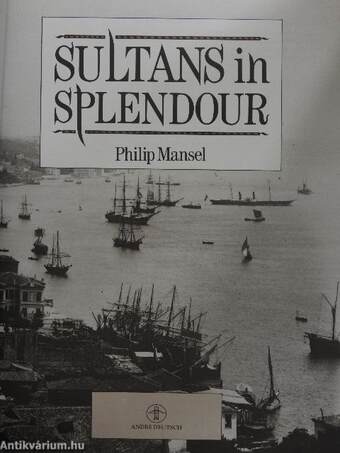

Sultans in Splendour

| Kiadó: | André Deutsch Limited |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | London |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Fűzött kemény papírkötés |

| Oldalszám: | 192 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | |

| Kötetszám: | |

| Nyelv: | Angol |

| Méret: | 28 cm x 22 cm |

| ISBN: | 0-233-98339-2 |

| Megjegyzés: | Fekete-fehér fotókkal. |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

Fülszöveg

Sultans in Sljlendour is a spectacular visual record of the end of an empire.

'If you want riches go to India. If you want learning, go to Europe. But if you want imperial splendour, come CO the Ottoman Empire. ' In 1869 the Khedive Ismail of Egypt, an Ottoman vassal, threw a round of glittering parties to celebrate the opening of the Suez Canal. Everybody was there: the Empress Eugénie of the French, the Emperor Francis Joseph of Austria, the Crown Prince Frederick William of Prussia. Desert chieftains prowled around waltzing Europeans and whirling dervishes, and dancing girls performed for the guests. It was a meeting of East and West which heralded the arrival of the modern age in the Middle East.

In 1869 the Ottoman Sultan ruled a powerful multinational empire stretching from the Danube to the Gulf. At its heart lay one of the largest and most cosmopolitan cities in the world: Constantinople, the city of the Sultans. By 1945 the Ottoman Sultans, and many other dynasties,... Tovább

Fülszöveg

Sultans in Sljlendour is a spectacular visual record of the end of an empire.

'If you want riches go to India. If you want learning, go to Europe. But if you want imperial splendour, come CO the Ottoman Empire. ' In 1869 the Khedive Ismail of Egypt, an Ottoman vassal, threw a round of glittering parties to celebrate the opening of the Suez Canal. Everybody was there: the Empress Eugénie of the French, the Emperor Francis Joseph of Austria, the Crown Prince Frederick William of Prussia. Desert chieftains prowled around waltzing Europeans and whirling dervishes, and dancing girls performed for the guests. It was a meeting of East and West which heralded the arrival of the modern age in the Middle East.

In 1869 the Ottoman Sultan ruled a powerful multinational empire stretching from the Danube to the Gulf. At its heart lay one of the largest and most cosmopolitan cities in the world: Constantinople, the city of the Sultans. By 1945 the Ottoman Sultans, and many other dynasties, had been overthrown, and most of the Middle East had been divided into the states which exist today. The Sultans and Kings had played a crucial part in this transformation, and their extraordinary position — between East and West — produced some memorable monarchs.

Abdul Hamid, the last of the great Sultans, who lived in the mysterious palace city of Yildiz, outside Constantinople, typified their dilemmas. A tyrant to many of his subjects, he was also a brilliant politician who maintained the independence of his empire at the height of European imperialism. From Morocco to Afghanistan, every monarch was under threat. People who appeared to be friends — Gordon of Khartoum, Lawrence of Arabia, Gertrude Bell — were also working to advance foreign interests. The British Empire was so powerful in the region that the last Ottoman Sultan left Constantinople on a British battleship.

Egypt, which replaced the Ottoman Empire as the leading monarchy in the area, faced similar problems. When King Farouk ascended the throne in 1936 he was the idol of his people, and de Gaulle described him as 'prudent, well-informed, quick-witted'. But by the time Farouk choked to death in a Rome restaurant he had become an obese debauchee who had lost his friends as well as his throne.

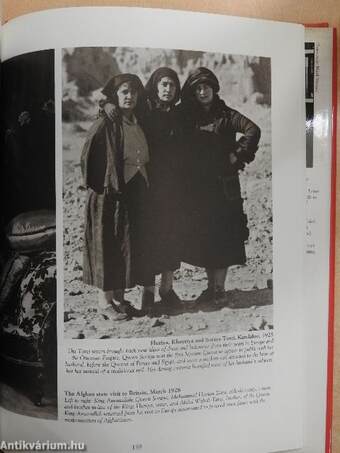

Weak or brutal, traditionalists or modernisers, the Ottoman Sultans and their rivals were never dull. Nor were they shy. They loved photography, and many of the two hundred unpublished photographs in this book come from dynastic collections. They reveal the way of life of the courts, the magnificence of the costumes and palaces and the forbidden world of the harem, with its eunuchs and Circassian slaves boughtifor the Sultan's pleasure.

'The whole volume is an important contribution to the understanding of people and events that are now beginning to be forgotten, but that played a significant part in the march towards the tangled and terrible tragedy of the Near Eastern World today '

Sir Steven Runciman Vissza

Témakörök

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Történelem > Európa története > Egyéb

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Történelem > Egyéb

- Történelem > Idegennyelvű > Angol

- Történelem > Legújabb kor > Egyéb

- Történelem > Kontinensek szerint > Ázsia, ázsiai országok története > Közel-Kelet

- Történelem > Kontinensek szerint > Európa, európai országok története > Dél-Európa > Egyéb

- Történelem > Újkor > Egyéb