1.118.325

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

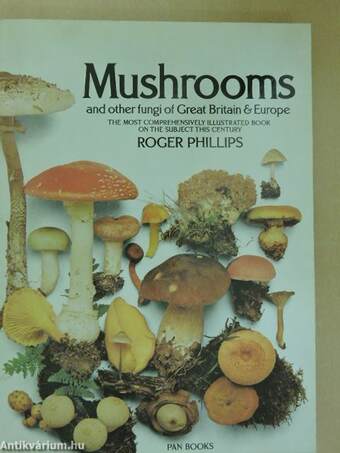

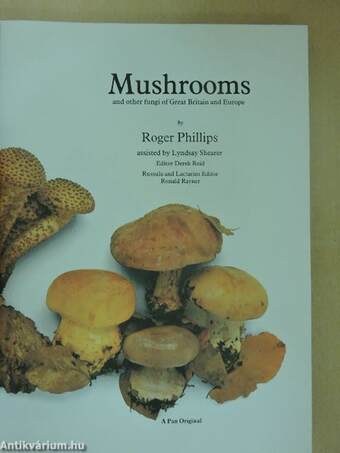

Mushrooms and Other Fungi of Great Britain and Europe

The most comprehensively illustrated book on the subject this century

| Kiadó: | Pan Books Limited |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | London |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Fűzött papírkötés |

| Oldalszám: | 287 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | |

| Kötetszám: | |

| Nyelv: | Angol |

| Méret: | 30 cm x 22 cm |

| ISBN: | 0-330-26441-9 |

| Megjegyzés: | Színes fotókkal gazdagon illusztrálva. |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

Előszó

Introduction

Mushrooms have become an obsession with me. In fact, after the work I have done on them over the last five years, I think I am qualified to call myself a fully fledged 'mushroom... Tovább

Előszó

Introduction

Mushrooms have become an obsession with me. In fact, after the work I have done on them over the last five years, I think I am qualified to call myself a fully fledged 'mushroom maniac'.

As a child I lived with my grandparents on their farm near Sarrat. In the autumn, the most exciting activity was mushroom collecting. I remember one year when we picked seventy pounds in a single day. My grandmother, however, would only allow us to eat the ordinary field mushrooms and she instructed me at great length in the dangers of even touching any other kind. This traditional fear that the Bridsh have of mushrooms is very deeply felt and tenaciously stuck to. Why?

In his revised introducuon to The Greek Myths, Robert Graves discussed the use of hallucinogenic mushrooms in rehgious ceremony. Is the British attitude a deeply ingrained tradition from Druidic times that mushrooms contain magical properties and may only be eaten under the control of the Druids themselves?

Far-fetched? Perhaps, but it needs a weird theory to explain our fears when you think how the nations that surround us rehsh eaung fungi of diverse kinds.

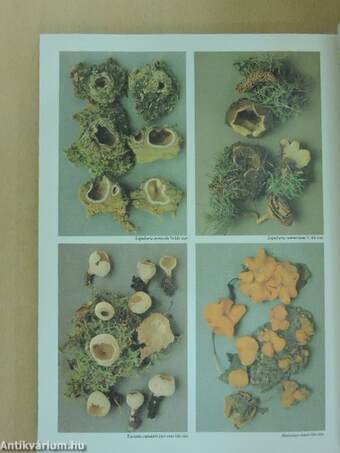

My first consideration in doing this book has been to produce as many illustrations as possible from the very large number of fungi to be found in Britain. In each photograph I have attempted, when I could find the species in sufficient quantity, to show all the salient aspects: the varieties of colour, size, age and details of stem and gills. The 914 species illustrated represent every fungus I, and all the mycologists who have helped me, have been able to find and identify over the last five years, excepting only those too old, damaged or incomplete to include.

Although the primary aim of this book is to be a visual guide, it is always important when trying to identify a specimen to check aspects that cannot be seen: the taste, smell, habitat and so on; and for those who wish to pursue their study in greater depth I have also incorporated informanon on the microscopy.

There are somewhere in the region of three thousand larger fungi to be found in the British Isles and the task of producing a complete set of photographs is impossible! For example, my photograph of Lentaria delicata (p.260) shows a fungus which has apparently not been collected since Fries described it in 1821. Then again, I made a collection of a small mushroom on the burnt heath near Wisley, which I found impossible to identify. However, after much study, Dr Derek Reid at Kew eventually came to the conclusion that it was a new species. This he has written up and sent for scientific publication in the Mycological Society Bulletin and hehasdone me the honour of naming it Galerina phillipsii (p. 157).

All this serves to demonstrate that there is still much work to be done in illustrating our fungi, and one day, in the distant future, perhaps I shall produce a second volume.

What is a mushroom?

A mushroom, or indeed any fungus, is only the reproducuve part of the organism (known as the fruit body), which

develops to form and distribute the spores. Fungi are a very large class of organisms which have a structure that can be compared to plants, but they lack chlorophyll and are thus unable to build up the carbon compounds essential to life. In fact, in the same way that animals do, they draw their sustenance ready-made from living or dead plants or even animals. A fungus is made up entirely of minute, hair-like filaments called hyphae. The hyphae develop into a fine, cobweb-like net and grow through the material from which the fungus obtains its nutrition. This is known as the mycelium. Mycelium is extremely fine and, in most cases, cannot be seen without the aid of a microscope. In other cases, the hyphae bind together to make a thicker mat which can readily be observed.

To produce a fruiting body, two myceUa of the same species band together in the equivalent of a sexual stage. Then if the conditions of nutrition, humidity, tempjerature and Ught are met, a fruit body will be formed. The larger fungi are divided into two distinct groups:

(i) The spore droppers, Basidiomycetes (pp. 15-264). In this group the spores are developed on the outside of a series of specialized, club-shaped cells (basidia)". As they mature, they fall from the basidia and are normally distributed by wind. Most of the fungi in this book are of this kind, including the gilled agarics, the boletes, the polypores and the jelly fungi.

(ii) The spore shooters, Asrnmycetes or_iAscos' (pp.264-281). The spores in this group are formed within club- or flask-shaped sacs (asci). When the spores have matured, they are shot out through the tip of the ascus. The morels, cup fungi and truffles are in this group.

Hedgehog Fungus Hydnum repandum (p.241)

How to use the book

Mushrooms and fungi are a large and very diverse group of organisms, and although this book only deals with the larger forms, there is nevertheless a bewildering selection to choose from. When you have leafed through the pages and got a general feel for the diversity of species that are illustrated, the next step in making an identification is to refer to the lists and keys (i-v) below: Vissza

Fülszöveg

A unique encyclopedia of mushrooms and other fungi found in the British Isles and Europe.

Full-colour photographs illustrate and identify more than 900 species, generally showing several specimens to indicate the various stages of growth.

Many of the species included have been photographed for the first time and make this the most comprehensively illustrated book on the subject published in Britain this century.

MUSHROOMS and other fungi

has been created by Roger Phillips whose companion volumes Wild Flowers, Trees and Grasses, Ferns, Mosses and Lichens are already established as international bestsellers.

A Pan Original

Tartalom

Contents

Introduction 6

Visual index 10

Glossary 14

Agarics

White spored 15

Pink spored 112

Brown spored 121

Black spored 158

Lateral stemmed 182

Gomphidiaceae 189

Chanterelles 190

Boletes 192

Polypores

Bracket forming 218

Crust forming 237

Toothed fungi 241

Puff-balls 246

Club fungi 256

Jelly fungi 262

Ascomycetes

Morels 264

Cup fungi 268

Truffles 279

Bibliography 282

Index 283

Témakörök

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Természettudományok > Földrajz

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Természettudományok > Egyéb

- Természettudomány > Növényvilág > Növénytan > Növényhatározó

- Természettudomány > Növényvilág > Növénytan > Rendszertan

- Természettudomány > Növényvilág > Növénytan > Növényföldrajz

- Természettudomány > Növényvilág > Kézikönyvek, határozók, lexikonok

- Természettudomány > Növényvilág > Gombák a természetben > Gombahatározó

- Természettudomány > Földrajz > Kontinensek földrajza > Téma szerint > Növényzet, állatvilág

- Természettudomány > Földrajz > Kontinensek földrajza > Topográfia szerint > Európa

- Természettudomány > Földrajz > Idegen nyelv > Angol

Roger Phillips

Roger Phillips műveinek az Antikvarium.hu-n kapható vagy előjegyezhető listáját itt tekintheti meg: Roger Phillips könyvek, művekMegvásárolható példányok

Nincs megvásárolható példány

A könyv összes megrendelhető példánya elfogyott. Ha kívánja, előjegyezheti a könyvet, és amint a könyv egy újabb példánya elérhető lesz, értesítjük.