1.072.879

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

VISSZA

A TETEJÉRE

JAVASLATOKÉszre-

vételek

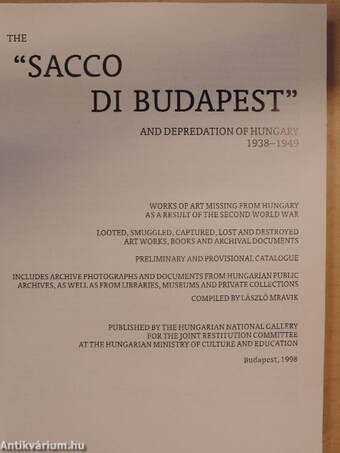

The "Sacco di Budapest" and Depredation of Hungary, 1938-1949

| Kiadó: | Hungarian National Gallery publications |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | Budapest |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Fűzött papírkötés |

| Oldalszám: | 468 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | |

| Kötetszám: | |

| Nyelv: | Angol |

| Méret: | 33 cm x 24 cm |

| ISBN: | |

| Megjegyzés: | Fekete-fehér fotókkal, reprodukciókkal. |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

Előszó

ON THE OCCASION OF A PREFACE-"AS YOU LIKE IT" I. THE LOSS OF THE ART WORKS This book is the prelimininary, and very much shortened, edition of a much larger, but as yet unfinished, work. At the... TovábbElőszó

ON THE OCCASION OF A PREFACE-"AS YOU LIKE IT" I. THE LOSS OF THE ART WORKS This book is the prelimininary, and very much shortened, edition of a much larger, but as yet unfinished, work. At the same time it constitutes official proof that research is being pursued in Hungary into art works and cultural treasures removed from the country in tempestuous times or taken abroad in some other unlawful manner. These were parts of Hungary's intellectual and cultural heritage, and, in our view, remain so today. When choosing the title we did not wish to be overpolite, since there was no reason to do so. We did not want to offend anyone, since the facts and events which took place provide no moral basis for offence to be taken, neither by countries, nor by instituions, nor by private persons. What we are addressing here is the fact that what happened in Hungary at the time of the Second World War was nothing short of looting, or to be more exact the carrying off and the smuggling abroad of art objects. It is important to mention this because everyone by and large has been accustomed to take offence, by not accepting the simple facts, but rather by substituting them with (false) interpretations and (erroneous) ideologies.^ When on the other hand we say to the culprits that they robbed the banks, looted and despoiled Hungarian country houses, and carried off gold and j ewellery belonging to the Jews, they are, of course, not pleased, and we do not expect them to be. We have, however, weighed these words and can use no others if we are to be true to history. After more than half a century, our hope is that as countries and institutions, if not as private individuals, we can begin to process the idea that we are the heirs to certain crimes. And if I may continue, the main offender was-let us finally say it-the Soviet Union, and its lawful successor. Yet even before the military authorities of the USSR carried of an appreciable proportion of Hungary's art treasures, very many others had already mutilated the country's cultural heritage. The story really begins with the legal measures depriving the country's Jews of their rights, measures which, from 1938 onwards, affected first their movable and non-movable property, later their freedom of movement, and finally, when they had nothing, their lives.2 After the German occupation of Hungary in the spring of1944 and the rise to power of the Hungarian fascists as a direct result of this, pillaging became general. This was even the case when thefts were taking place in a less overt way. Art treasures owned by Jews were sequestrated and collected together centrally, but every piece was handled in the knowledge of who its owner was.3 The situation became chaotic only when it became clear that Soviet troops would shortly encircle the Hungarian capital. In late November and early December 1944 the Szalasi government, which had come to power in what can only be described as a coup, began to evacuate the most important art works and books in Hungarian public collections to the territory of the Third Reich. Together with these it took the greater part of the art works owned by Jews, other valuables and objects associated with Hungarian statehood, namely the Hungarian coronation insignia and the precious metal and precious gem reserves of the National Bank of Hungary. The German military used its occupation of Hungary not only to augment Germany's strategic reserves, but also to increase its own wealth, by whatever means. In almost all cases, the gold, silver and platinum items of Hungarian Jews living outside Budapest passed into the hands of the German officers entrusted with the implementation of the Final Solution.4 It was common knowledge that shortly after the German occupation the Jews outside the capital had been almost totally liquidated. The clumsy steps taken by the Hungarian authorities to prevent this were almost totally ineffective. Indeed, the Hungarian gendarmerie liberally assisted the Germans in the deportations and in the plundering. However, there were no important art works among the objects stolen by the Germans at this time, since there were few art collectors of any note among the Jews of the small towns and villages. Shortly afterwards legal measures were introduced enabling the Hungarian state to sequester works belonging to Jews, and Hungarian officials j ealously monitored all German actions which would have violated these laws.5 This attitude was dictated by pure logic, because the war was already surely lost, because they would in all probability be called to account when the hostilities were over, and also because most Hungarian officials were anti-German in sentiment.6 Many thought-not without reason-that by sequestering Jewish property they could save it for its owners. For their part, Ferenc Szalasi and his entourage took the view that they were stealing from their own Jews, and did not want to share the loot with the Germans. But among the leading Hungarian Nazis close to Szalasi there were many (Endre Baky, for example) who helped the Germans in their quest for art treasures.7 During the German withdrawal and the socalled Winterhilfe operation which preceded it, Nazi officers carried off an enormous number of art treasures from Jewishowned villas. These were collected together in Buda and then taken, in convoys of lorries or by rail, to Austria. By this time no-one asked the opinion of the Hungarian authorities. Those art works which they were unable to evacuate the Germans set alight along with the Mauthner villa in Buda, displaying an example of barbarism not seen in Hungary in more than 400 years. VisszaTartalom

CONTENTSOn the Occasion of a Preface - "As You Like It" - 7

REFERENCES

Abbreviations - 20

Important Auctions - 22

Important Exhibitions up to 1945 - 25

A History of Hungarian Art Collections, 15th-20th centuries

Selected Literature & Other References - 30

Index of More Important Place-names - 56

SELECTED DOCUMENTS

Document No. 1. Law XI of 1929 (Extracts), Laying Down, in

Clear Terms, the Regulations in Force from 1929 until 1953

Governing Cultural and Artistic Treasures in Private Ownership - 58

Document No. 2. General Orders to the Administrative

Authorities on the Taking Over of Property Sequestered from

Jews, and on the Drawing Up of Inventories of Homes, Shops,

Warehouses, Etc. Abandoned by Jews - 60

Document No. 4. "Priceless Art Collections of Baron Alfonz

Weiss and the Herzog Brothers Found in Budafok Cellars".

Newspaper article -68

Document No. 5. "What Should be Done With Jewish Picture

Collections So Carefully Concealed from the Public?" Newspaper article - 70

Document No. 19. Declaration by Samu Stern, President of

the Jewish Community of Pest - 73

Document No. 20. Memoranda Drawn Up at the Italo-Hungarian Bank Concerning the Activity of the Russian Economic Officers' Commission - 74

Document No. 21. Minutes Taken at the Industry Secretariat

of the Hungarian Commercial Bank of Pest (the Russian military authorities had taken away valuables without giving a

receipt for what had been taken) - 75

Document No. 22. List of the Locked Deposits at the Hungarian Commercial Bank of Pest Taken as War Booty by the Soviet Economic Officers' Commission-76

Document No. 25. Correspondence of Dr. Andor Ullmann in

the Matter of Art Works of His Taken Away by the Soviet

Authorities - 87

Document No. 26. Letter from Hungarian Minister of Religion and Public Education Geza Teleki to Marshal Voroshilov,

President of the Allied Control Commission - 89

Document No. 27. Summary Prepared by the Ministry of Religion and Public Education on Soviet War Booty Taken from

the Vaults of Budapest Banks - 90

Document No. 29. Report to the Hungarian Minister of Religion and Public Education by Pál C. Voit on Museums, Museum Collections and Works of Art in Private Possession-100

Document No. 33. Letter from the Hungarian Prime Minister

to Marshal Voroshilov, President of the Allied Control Commission-105

Document No. 41. The Case of the Strong-room Compartment Rented by the Government Commission for Art Works

Sequestered from Jews -106

Document No. 43. Annotated Inventories for Chests Deposited at Banks by Baron Ferenc Hatvany-109

Document No. 44. Letter from Sándor Jeszenszky, Ministerial Commissioner and Retired Departmental Head at the Ministry of Religion and Public Education, to Mme. Andrea

Domán, of the Art Collecting Point, Munich -112

Document No. 48. Report to the Minister of Religion and Public Education by the Ministerial Commissioner for Works of

Art Taken from Public and Private Collections on His One

Year's Activity-113

Document No. 51. Sándor Jeszenszky Calls the Attention of

Minister Gyula Ortutay to the Illegal Export of Certain Pieces

from the Herzog Collection -115

Document No. 55. Summary Report by Dr. Tamás Bogyai Concerning His Activities So Far, the Situation Regarding Works

of Art Taken to the West, and Actions To Be Taken -117

Document No. 56. Letter from Dr. Tamás Bogyay to Dr. Erik

Fügedi, Ministerial Commissioner for Endangered Private

Collections, Concerning the Search for One-time SS Officers

Accused of Taking Away Hungarian Works of Art-122

Document No. 64. Memorandum drawn up in 1965 by the

Foreign Currency and Deposits Department of the Centre for

Monetary Institutions for General Manager Dr. Dezséri, on

Information Available in the Affair of the Compensation Case

Brought In Germany in Connection with the Ferenc Hatvany

Collection -123

Document No. 68. Memorandum for General Manager Dr.

Dezséri Drawn Up in 1966 by the Foreign Currency and

Deposits Department of Budapest's Centre for Monetary

Instititions Concerning Information It Had in Connection

with the Hatvany Compensation Affair-124

Document No. 69. Memorandum from the Centre for Monetary Institutions on the Findings of the Search Mounted in the

Veszprém Archives in Connection with Ferenc Hatvany's Art

Works (1968)-126

Document No. 71. Miksa Fried's Official Staement Before a

Notary on the Looting of the Vida Villa in Buda -127

Document No. 73. Memorandum from the Centre for Monetary Insitutions for Rezső Nyers, Secretary of the Central

Committee of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, for His

Information -128

Document No. 75. Correspondence in Connection with Paintings Returned to Hungary by the Soviet Union. Top secret

until very recently -130

Document No. 78. The Sack of the Swedish Embassy in

Budapest by the Economic Officers' Commission of the Red

Army-134

Document No. 79. Agreement Between of the State Commissions of the Republic of Hungary and the Russian Federation

for the Return of Cultural Property Concerning Co-operation

in the Return of Cultural Property Taken to the Territory of the

Other During and After the Second World War -135

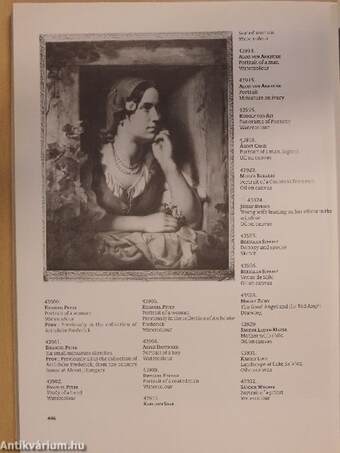

PROVISIONAL CATALOGUE (THE COLLECTIONS)

Counts Gyula Andrássy the Elder and Younger -139

Dr. Rudolf Bedő -148

Dr. Gyula Bencze -149

Aurél Bemáth -151

Mária and Antónia Bezerédj -152

János Biehn -155

Árpád Biró -162

Henrietta Bíró de Hámor -163

Dr. László Brázay -165

Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts -166

Dr. Ferenc Chorin -168

Count Endre Csekonics -170

Dr. József Csetényi -171

Baron Andor Dirsztay -182

Count Móric Esterházy-191

Dr. István Eszláry-192

Sándor Fancsikay-192

Dr. Henrik and Pál Fellner -193

Dr. József Fleissig-195

Baron Dezső Forster-195

Dr. Ignác Friedmann - 196

Dr. Fülöp Grünwald - 209

Dr. László Gullya -209

Baron Sándor Harkányi - 210

Baron Bertalan Hatvany-213

Baron Ferenc Hatvany-223

Baroness JózsefHatvany and Baron Endre Hatvany-276

Mme. Henrik Herz - 303

Baron Mór Lipót Herzog - 305

Dr. Leó Holländer-350

Baroness Adolf Kohner-351

Baron Móric Kornfeld - 353

Dr. László Laub - 362

Dr. Zoltán Máriássy-367

Prince Nándor Montenuovo - 373

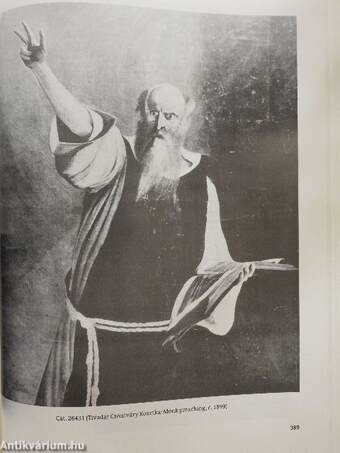

Dr. Miklós Moskovits - 380

Dr. Bertalan Neményi - 383

Dr. Alfréd Perimutter - 397

Prime Minister's Official Residence (Property of the Hungarian State)- 401

I

Library of the Calvinist College at Sárospatak - 404

Miksa Schiffer-406

Bishop Laj os Shvoy - 409

Mme. Tivadar Solténszky-410

Mme. Sándor Kisbábi Strasser, née Selma (Zelma) FröhlichFeldau-411

Dr. Pál Strauss - 440

Dr. Dezső Szeben-442

Zsigmond Szegő-448

Szentiványi Castle, Bélád-450

Béla Szerdahelyi - 450

Vilmos Szilárd-450

Dr. Andor Ullmann-451

INDEX OF ARTISTS - 458

Témakörök

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Művészetek > Művészettörténet, általános

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Művelődéstörténet

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Vendéglátás, kereskedelem

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Történelem > Európa története > Magyarország története

- Művelődéstörténet > Kultúra > Kultúrpolitika

- Művelődéstörténet > Átfogó művek, tanulmányok

- Művészetek > Művészettörténet általános > Múzeumok, képtárak > Magyar > Egyéb

- Művészetek > Művészettörténet általános > Idegen nyelv > Angol

- Művészetek > Művészettörténet általános > Művészettörténet > Magyar

- Művészetek > Művészettörténet általános > Kiállítások, aukciók, katalógusok > Magyar > Egyéb

- Művészetek > Művészettörténet általános > Tanulmányok > Magyar

- Történelem > Idegennyelvű > Angol

- Történelem > Levelek, forráskiadványok, dokumentumok > XX-XXI. század

- Történelem > Magyarország története és személyiségei > Magyarország a XX. században > II. világháború > Hadtörténete

- Történelem > Magyarország története és személyiségei > Magyarország a XX. században > A II. világháború utáni Magyarország > Egyéb

- Történelem > Politika > Külpolitika > Diplomácia

- Történelem > Magyarország története és személyiségei > Magyarország a XX. században > II. világháború > Holokauszt

- Történelem > Hadtörténet > Hadügy, hadviselés

- Vendéglátás, kereskedelem > Műtárgy kereskedelem

Megvásárolható példányok

Nincs megvásárolható példány

A könyv összes megrendelhető példánya elfogyott. Ha kívánja, előjegyezheti a könyvet, és amint a könyv egy újabb példánya elérhető lesz, értesítjük.