1.067.317

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

VISSZA

A TETEJÉRE

JAVASLATOKÉszre-

vételek

An Eye for an Eye

The Untold Story of Jewish Revenge Against Germans in 1945

| Kiadó: | BasicBooks |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | New York |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Félvászon |

| Oldalszám: | 252 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | |

| Kötetszám: | |

| Nyelv: | Angol |

| Méret: | 24 cm x 16 cm |

| ISBN: | 0-465-04214-7 |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

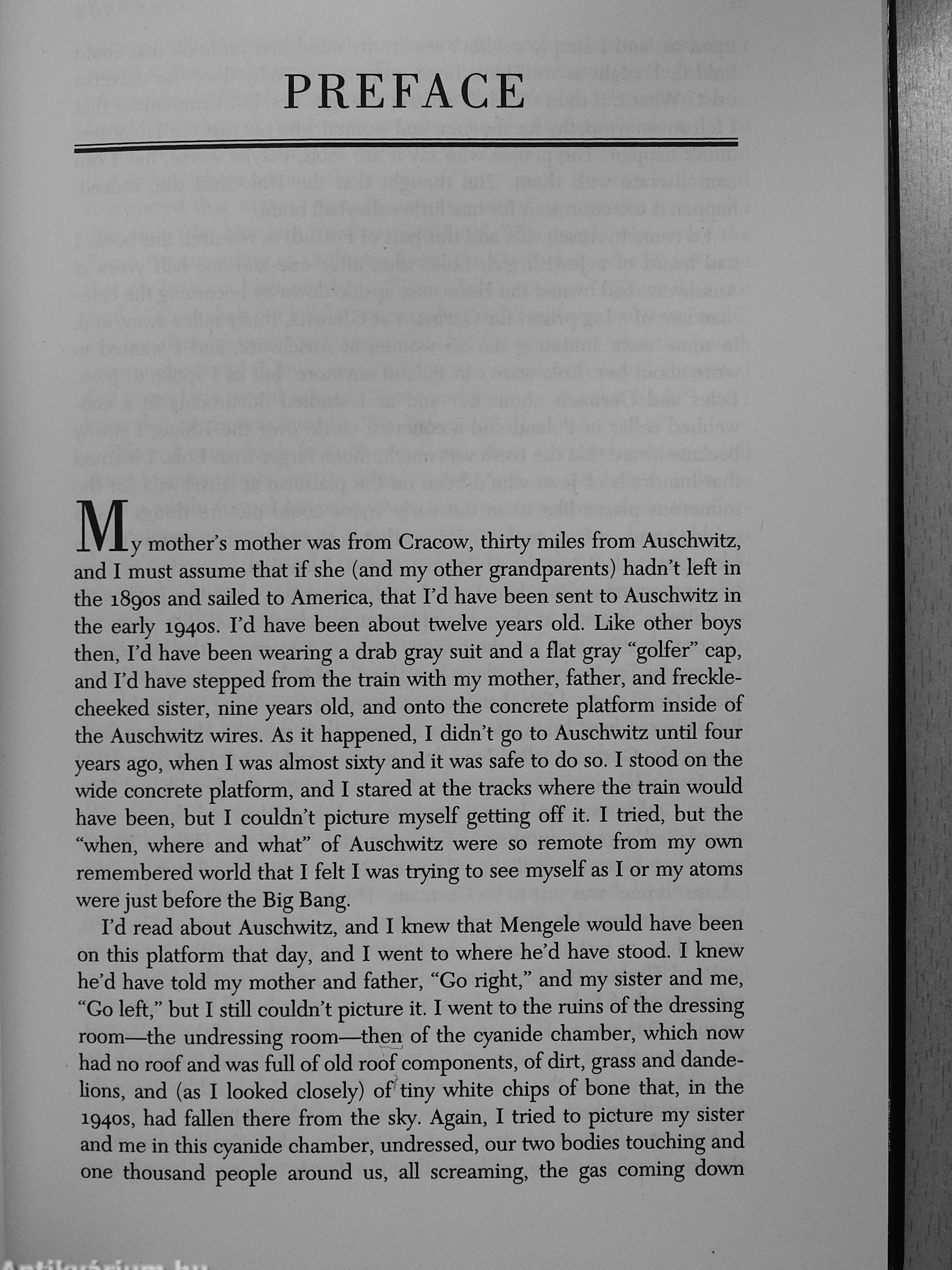

Előszó

TovábbFülszöveg

The worst thing that happened to some Holocaust survivors was that they became like Nazis. How and why—and why they stopped—is the subject of this book. It is a story of Jewish revenge—and Jewish redemption.

An Eye for an Eye is a riveting account of the appalling events that accompanied the end of World War II. In 1945 the Soviet Union, which occupied Poland and parts of Germany, a region inhabited by ten million German civilians, established the Office of State Security and deliberately recruited survivors of the Holocaust to carry out a policy of de-Nazification. The Office entered German homes and rounded up German men, women, and children—99 percent of them noncom-batant, innocent civilians—and took them to cellars, prisons, and 1,255 concentration camps, where inmates subsisted on starvation rations, where typhus ran rampant, and where torture was commonplace. In this brief period, between 60,000 and 80,000 Germans died in the Office s custody.

The book tells the story of... Tovább

Fülszöveg

The worst thing that happened to some Holocaust survivors was that they became like Nazis. How and why—and why they stopped—is the subject of this book. It is a story of Jewish revenge—and Jewish redemption.

An Eye for an Eye is a riveting account of the appalling events that accompanied the end of World War II. In 1945 the Soviet Union, which occupied Poland and parts of Germany, a region inhabited by ten million German civilians, established the Office of State Security and deliberately recruited survivors of the Holocaust to carry out a policy of de-Nazification. The Office entered German homes and rounded up German men, women, and children—99 percent of them noncom-batant, innocent civilians—and took them to cellars, prisons, and 1,255 concentration camps, where inmates subsisted on starvation rations, where typhus ran rampant, and where torture was commonplace. In this brief period, between 60,000 and 80,000 Germans died in the Office s custody.

The book tells the story of what drove people who had been through unimaginable suffering to turn around and inflict the same on others. John Sack focuses on people like Lola, a young woman who became commandant of a prison, determined to avenge the death of her mother, brother, sister, and one-year-old baby . . . Pinek, Lolas gentle childhood friend who after the war became head of security for all of Silesia but never saw what was going on in his jurisdiction and, bitter because it had ignored Auschwitz, refused to allow the Red Cross to come and look . . . and Shlomo, a commandant who

{continued on back flap)

(continued from front flap )

bragged that "What the Germans couldn't do in five years at Auschwitz, I've done in five months at Schwientochlowitz." (In fact, his arithmetic was faulty: the Germans at Auschwitz killed just as many people in five short hours.)

Nothing has ever been written about this. To unearth the story, the author spent seven years doing research and conducting interviews in Poland, Germany, Israel, and the United States. Sixty-five pages of notes and sources testify to the accuracy of the reporting.

"I read this extremely gripping and compelí g account of the appalling events which accompanied the end of the war and the expulsion of the Germans, from what was to become Westen Poland in one go. It was impossible to put down. . . . The topic of Jewish participation i i these acts of oppresMon is controversial, but, in ny view, only two questions need to be raised, lie first concerns the motivation of the author arid here I am Convinced that Mn Sack has tried, as he himself writes, to tell 'something more than the story of Jewish revengd: the story of Jewish rédemption.' The second is^whether the story is rue a.nd what it is based pn^ Here, too, Tam satis-ied tHat the author is a serious^ researcher . The )ok is in fact a major contribution to our under-tiiding. I certainly recommeiid publication.'

¦ I, ' ¦

—Antony polonsk^ Professor of East European Jewish Histon I RranHfiis TlmVersih Vissza

Témakörök

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Szépirodalom > Megtörtént bűnügyek, dokumentumregények

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Szépirodalom > Regény, novella, elbeszélés

- Szépirodalom > Regény, novella, elbeszélés > Tartalom szerint > Történelmi regények > Koncentrációs táborok, holokauszt

- Szépirodalom > Regény, novella, elbeszélés > Tartalom szerint > Történelmi regények > Hadifogság, lágerek

- Szépirodalom > Regény, novella, elbeszélés > Tartalom szerint > Történelmi regények > Legújabb kor > Egyéb

- Szépirodalom > Regény, novella, elbeszélés > Tartalom szerint > Életrajzi regények > Önéletrajzok, naplók, memoárok

- Szépirodalom > Megtörtént bűnügyek, dokumentumregények

John Sack

John Sack műveinek az Antikvarium.hu-n kapható vagy előjegyezhető listáját itt tekintheti meg: John Sack könyvek, művekMegvásárolható példányok

Nincs megvásárolható példány

A könyv összes megrendelhető példánya elfogyott. Ha kívánja, előjegyezheti a könyvet, és amint a könyv egy újabb példánya elérhető lesz, értesítjük.