1.067.317

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

VISSZA

A TETEJÉRE

JAVASLATOKÉszre-

vételek

The Iliad of Homer

| Kiadó: | Walter J. Black, Inc. |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | New York |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Vászon |

| Oldalszám: | 391 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | Classics Club |

| Kötetszám: | |

| Nyelv: | Angol |

| Méret: | 19 cm x 14 cm |

| ISBN: | |

| Megjegyzés: | Néhány fekete-fehér illusztrációval. |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

Előszó

INTRODUCTION Sometime about

thirty-six or thirty-seven hundred years ago, historians say, the first

Greek tribes of whom we have any knowledge came down from the

northern mountains into the... Tovább

Előszó

INTRODUCTION Sometime about

thirty-six or thirty-seven hundred years ago, historians say, the first

Greek tribes of whom we have any knowledge came down from the

northern mountains into the coasts and plains of what was later called

Greece. They did not call themselves Greeks but Achaeans or, some-

times, Danaans, the folk, that is, of a mythical King Danaus, prolific

in daughters. They were a bold, untamed, half-civilized race, but the

people they proceeded to conquer had for some centuries been part

of a rich Aegean civilization, centered in the southern island of Crete.

The Achaean freebooters took over the strongholds of the Aegeans

and gradually many of their arts and habits of life, keeping, however,

certain ideas and practices of their own which made their culture at

various points different from that of the Aegeans before them. It took

them years to complete the conquest. Even then they remained for a

long time a warlike breed, living off the older population of workers

on the soil. When too much peace grew monotonous, they fought

among themselves or sailed away on piratical expeditions up and

down the surrounding seas. In leisure hours they listened to tales of

their own Achaean heroes and their exploits by land and water or of

their gods and goddesses and their miraculous participations in hu-

man affairs.

So the time passed. Eventually the Achaeans grew interested in

the cultivation of their acquired fields and vineyards, their herds of

cattle, sheep and swine. They learned to combine piracy with trade

and made the acquaintance of the highly developed civilizations of

Phoenicia and Egypt. Then, somewhere about the year 1100 b.c.,

their dominion was shaken by new migrations of northern Greeks,

who came as they had once come, streaming down from the moun-

tains, through Thessaly and on to the south. But this time one in-

vasion followed hard on another. At least two centuries were filled

XJ Vissza

Tartalom

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION. By Louise R. Loomis n

PREFACE. By Samuel Butler 1X12

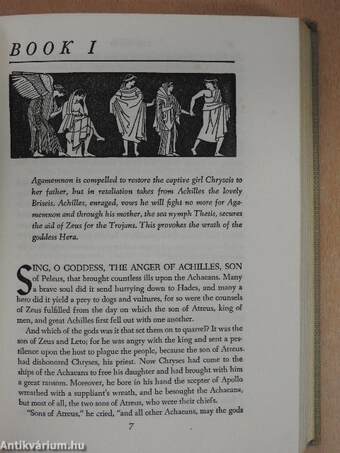

BOOK I: Quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon. Achil-

les withdraws in anger from the war, and secures Zeus' aid for

his enemies, the Trojans. 7

BOOK II: Agamemnon's dream causes him to test his men.

Nestor and Odysseus incite the army to fight. Both sides "pre-

pare for battle. 22

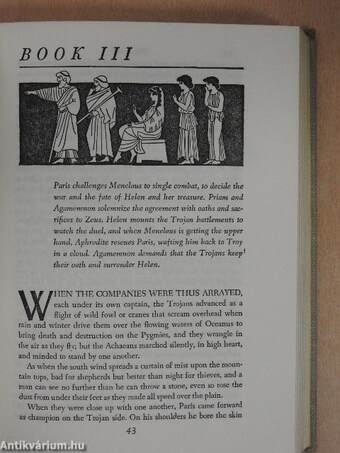

BOOK III: Menelaus challenges Paris to single combat to

decide the war. Sacrifices are made to solemnize the truce. Paris

is rescued from defeat by Aphrodite. 45

BOOK IV: The Gods decide to intervene. Athene comes

from Olympus and incites Pandoras to break the truce. Aga-

memnon marshals his men. 54

BOOK V: Diomed performs great exploits with the help of

Athene. Ares, who aids the Trojans, is finally driven from the

field. 67

BOOK VI: Hector goes back to Troy to offer sacrifices. He

comforts Andromache and rebukes Paris, whom he finds with

Helen. The brothers return to the fray. 88

BOOK VII: Hector and Ajax meet in single combat, which

is halted by nightfall. The Greeks build a wall. Paris refuses

to give up Helen. 10*

BOOK VIII: Zeus forbids the gods to intervene. The Greeks

are forced back behind their wall, leaving the Trojans in com-

mand of the field. 1x3

vrn

THE ILIAD

BOOK DC: Agamemnon proposes a return to Greece. He is

chided by his chiefs. Achilles, besought, refuses to reenter the

fight. 127

BOOK X: In the night Agamemnon sends Diomed and

Odysseus to spy on the enemy. They learn the disposition

of forces and kill King Rhesus. 144

BOOK XI: Agamemnon leaves the field wounded:. Hector

leads the Trojans forward and the Greeks retreat. Nestor of-

fers a plan for deceiving the Trojans. 158

BOOK XII: The Trojans assail the wall on foot. The de-

fense is headed by the two Ajaxes. The Trojans pour over the

wall. 179

BOOK XIII: Poseidon, angered with Zeus, rallies the Greeks.

Idomeneus performs valorous deeds. Still the Trojans advance. 191

BOOK XIV: The Greeks are hard pressed. Hera, to distract

Zeus from aiding the Trojans, entices him to Mount Ida. The

fortunes of battle now favor the Greeks. 212

BOOK XV: Zeus, discovering Hera's guile, tells her the

Greeks will conquer Troy. Hector leads another attack, and

Achilles is told of the danger. 225

BOOK XVI: Patroclus, wearing Achilles' armor, puts the

Trojans to flight. In the pursuit he is disabled by Apollo,

then slain by Hector. 243

BOOK XVII: Trojans and Greeks struggle over the body of

Patroclus. The Greeks finally capture the body and make for

the ships. 265

BOOK XVIII: Achilles, enraged by Patroclus'death, decides

to reenter the conflict. Thetis asks Hephaestus to make him

new armor. 283

contents

IX

BOOK XIX: Agamemnon and Achilles are reconciled. The

Greeks prepare for battle. Achilles is warned of approaching

death. 298

BOOK XX: Zeus tells the gods they may take, part in the

war. Apollo incites Aeneas to attack Achilles, who slaughters

countless Trojans. 308

BOOK XXI: Angered by Achilles' carnage the River Sea-

mander overflows. The gods battle each other on the field. The

routed Trojans flee behind their wall. 321

BOOK XXII: Hector stands alone to face Achilles. He flees,

then turns and fights, tricked by Athene, and is slain. The

Trojans mourn. 336

BOOK XXIII: Achilles drags Hector's body to the Greek

camp. Sacrifices are offered in honor of Patroclus and funeral

games are held. 350

BOOK XXIV: Guided by Hermes, Priam goes to the Greek

camp to ransom Hector's body. Achilles, moved to pity, gives

it up. Hector's funeral is celebrated. 372

Témakörök

Megvásárolható példányok

Nincs megvásárolható példány

A könyv összes megrendelhető példánya elfogyott. Ha kívánja, előjegyezheti a könyvet, és amint a könyv egy újabb példánya elérhető lesz, értesítjük.