1.069.245

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

VISSZA

A TETEJÉRE

JAVASLATOKÉszre-

vételek

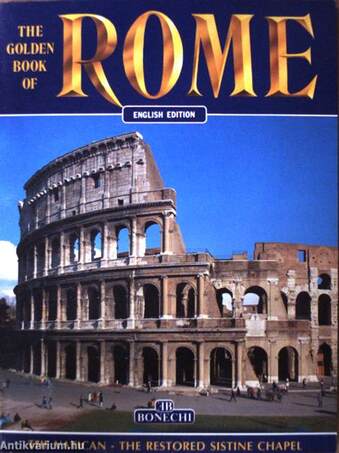

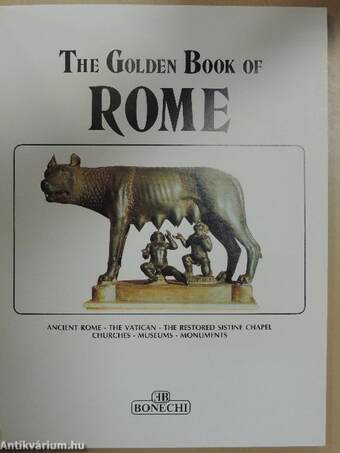

The Golden Book of Rome

Ancient Rome - The Vatican - The restored Sistine Chapel - Churches - Museums - Monuments

| Kiadó: | Casa Editrice Bonechi |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | Firenze |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Varrott papírkötés |

| Oldalszám: | 123 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | The Golden Book |

| Kötetszám: | |

| Nyelv: | Angol |

| Méret: | 26 cm x 20 cm |

| ISBN: | |

| Megjegyzés: | Színes fotókkal gazdagon illusztrálva. |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

Előszó

HISTOR Y Rome began when groups of shepherds and farmers settled on the hill now known as the Palatine. Etymologically Roma may mean the city of the river, or more probably the city of the Ruma, an... TovábbElőszó

HISTOR Y Rome began when groups of shepherds and farmers settled on the hill now known as the Palatine. Etymologically Roma may mean the city of the river, or more probably the city of the Ruma, an old Etruscan family. After the semi-legendary period of the monarchy, the first authentic historical references date to the moment of transition from the monarchy to the republic (509 B. C.), when the Etruscan civilization, which had dominated Romé with the last kings, began its slow decline. The long period of the republic was marked by the formation of a real democracy governed by the consuls and the tribunes (the former represented the so-caUed plebeians), which went so far as to institute equal rights for patricians and plebs. In the 4th century B.C. Romé already held sway over all of Latium and laler extended its rule lo many other regions in Italy, subjugating numerous Italic peoples and the great Etruscan civilization. Even the Gauls, and the Greeks in southern Italy, laid down their arms to Romé and by 270 B.C. the entire Italian peninsula had fallen under Román domination. In the 3rd century B.C. this power began to spread out beyond the borders of the peninsula. Between 264 and 201 B.C. the entire Mediterranean (with the Punic wars) feli under Román rule, and in the east, Romé extended its frontiers into Alexander the Great 's kingdom, and in the west, subjugated the Gauls and the peoples of Spain. It is at this point that the republic became an empire, beginning with auspices of power and greatness under Augustus. The empire, as it was conceived, was meant to be a balanced mixture of the various republican magistratures under the direct control of the senate and the will of the people. This was what it was meant to be, but in reality as time passed the empire took on an ever increasing dictatorial and militaristic aspect. With its far-flung frontiers, Romé found itself divided and split and as its authority began to wane, it went into a slow but inexorable decadence. The city was no longer the emperor's seat and the senate continued to lose its poiitical identity. This decadence reached its zenith after the first barbarian invasions, but the city never lost its morál force, that awareness which for centuries had considered Romé the caput mundi, a situation which was alsó abetted by the advent of Christianity which consecrated it as the seat of its Church. After the middle of the 6th century A.D., Romé became just another of the cities of the new Byzantine empire, with its capital in Ravenna. Even so, two centuries later, thanks to the presence of the Popé, it once more became a reference point for this empire and its history becomes inseparable from that of the Franco-Carolingian empire. Charlemagne chose lo be crowned emperor in Romé and hereafter all emperors were to be consecrated as such in Rome. The city prodaimed itself a free commune in 1144. In this period it was governed by the municipal powers, the papacy and thefeudal nobility. The powers of the commune and those of the popé were often in open contrast and were marked by harsh struggles. At the beginning of the 14th century the papacy moved to Avignon and the popular forces were freer to govern. At the end of the 14th century and in the early 15th century the situation once more was reversed: the popé returned to Rome and managed to gain control of the city and recuperate most of the power the popular government had gained in the preceding century. The city flourished in this period, for it became the capital of the Papai State and was as splendid as ever, one of the most important crossroads for culture and art. In the centuries that followed, politically Rome tended towards an ever greater isolation: the Papai State kept at a distance from the various international contrasts and while this set limits on its importance from a poiitical point of view it gave free rein to a development of trade and above all the arts and culture. This situation continued up to the end of the 18th century when the revolutionary clime which struck Europe in those years alsó invoIved the Church in an unexpected crisis and the papai rule of the city passed to the Republic (Pius VI was exiled to Francé). Temporal power had a brief comeback with Pius VII, but only a few years later Napoleon once more revolutionized the situation, proclaiming Rome the second city of his empire. After varying vicissitudes in which the city returned to the popé (1814), came the period of the Risorgimento when, under the papacy of Pius IX, Rome was a ferment of patriotic and anticlerical ideals. In 1848 a real parliament was förmed; the following year the Román Republic was prodaimed and the government passed into the hands of a triumvirate headed by Giuseppe Mazzini until the intervention of the French army restored temporal power. In 1860 with the formation of the Kingdom of Italy, the pope's power was limited to Latium alone. Ten years later, with the famous episode ofthe breach at Porta Pia, the French troops protecting the papacy were driven out of the city, which was annexed to the Kingdom of Italy and became its capital. Dissension arose between the Papa! State and the new Italian poiitical reality which eventually led to the conciliation between the State and the Church in the Lateran Paci (Feb. 11, 1929). After World War II, when Italy passed from the monarchy to the republic, Rome became the seat of the Italian Parliament. ARCHITECTURE In the beginning Rome developed on the Palatine hill and gradually spread to the surrounding hills. The Servian walls date to the 4th century B.C.. The circuit o/Aurelian walls are later. The úrban fabric changed almost radically during the felicitous period of the Republic and the city s VisszaTartalom

INDEXIntroduction P- 3

Plan of the Forums » 20

Plan of the city » 126

PART I

THE CENTER OF ROMÉ » 5

PART II

ANCIENT ROMÉ » 12

PART III

MONUMENTAL ROMÉ » 66

PART IV

THE VATICAN » 86

PART V

THE BASILICAS » 106

Appia Antica and Tomb of Caecilia Metella » 118

Arch of Constantine » 59

Arch of Septimius Severus » 31

Arch of Titus » 45

Basilica Aemilia » 24

Basilica Júlia » 34

Basilica of Maxentius » 43

Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano » 110

Basilica of San Lorenzo fuori le Mura » 114

Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore » 106

Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano » 87

Basilica of San Pietro in Vincoli » 108

Baths of Caracalla » 117

Capitoline » 5

Castel Sant'Angelo » 84

Catacombs » 118

Church of Santa Francesca Romana » 44

Church of San Marco » 8

Church of Santa Maria d'Aracoeli » 8

Church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin » 63

Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere » 114

Church of Santa Maria di Loreto e

Santissimo Nome di Maria » 10

Circus Maximus » 60

Colosseum » 50

Column of Marcus Aurelius » 69

Curia » 28

Elephant in Piazza della Minerva » 69

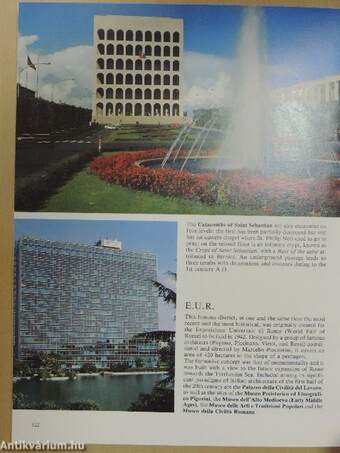

E.U.R » (22

Forum of Augustus » 17

Forum of Caesar » 18

Forum of Nerva

Forum, Román

Forum of Trajan

Forums, Imperial

Fountain of Trevi

Fountain of the Triton

House of the Vestals

Isola Tiberina

Mamertine Prisons

Mausoleum of Augustus

Monument to Victor Emmanuel II

Museum and Galleria Borghese

Palatine

Palazzo del Quirinale and della Consulta

Vatican Palaces

Palazzo di Giustizia

Palazzo Venezia

Pantheon

Piazza Navona

Piazza del Popolo

Piazza San Pietro

Piazza di Spagna and Trinitá dei Monti .

Pincio

Pyramid of C. Cestius

Scala Santa

Sistine Chapel

Stanze of Raphael

Synagogue

Temple of Antoninus and Faustina

Temple of Castor and Pollux

Temple of Divus Julius

Temple of Divus Romulus

Temple of Saturn

Temple of Venus and Roma

Temple of Vesta

Theater of Marcellus

Tivoli

» Hadrian's Villa

» Villa d'Este

Trajan's Markets

Vatican Palaces

Via Sacra

Via Veneto

Villa Borghese

Témakörök

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Művészetek > Fotóművészet

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Útikönyvek

- Útikönyvek > Európa > Fővárosai

- Útikönyvek > Európa > Dél-Európa > Városai

- Útikönyvek > Idegennyelvű útikönyvek > Angol

- Útikönyvek > Utazás, turizmus

- Útikönyvek > Természetjárás, túrák > Városnézés

- Művészetek > Fotóművészet > Albumok > Külföldi

- Művészetek > Fotóművészet > Albumok > Tematikus

- Művészetek > Fotóművészet > Idegen nyelv > Angol

- Művészetek > Fotóművészet > Témái > Városok > Külföldi

Megvásárolható példányok

Nincs megvásárolható példány

A könyv összes megrendelhető példánya elfogyott. Ha kívánja, előjegyezheti a könyvet, és amint a könyv egy újabb példánya elérhető lesz, értesítjük.