1.062.916

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

VISSZA

A TETEJÉRE

JAVASLATOKÉszre-

vételek

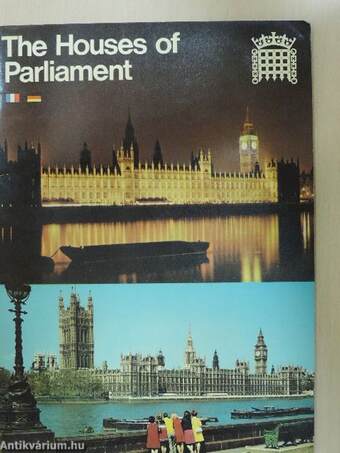

The Houses of Parliament

| Kiadó: | Jarrold Colour Publication |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | Norwich |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Tűzött kötés |

| Oldalszám: | 32 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | |

| Kötetszám: | |

| Nyelv: | Angol |

| Méret: | 25 cm x 18 cm |

| ISBN: | 85306-655-8 |

| Megjegyzés: | Színes fotókkal. |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

Előszó

When, in 1834, the Palace of Westminster was almost entirely destroyed by fire, there perished a building which had been, since an early date before the Norman Conquest, first the royal residence... TovábbElőszó

When, in 1834, the Palace of Westminster was almost entirely destroyed by fire, there perished a building which had been, since an early date before the Norman Conquest, first the royal residence of the King and the seat of his government, then the chief law court of the country and, eventually, and most important, after 1547, the meeting-place of the two Houses of Parliament. The old Palace of Westminster had been the scene of innumerable occasions of deep historical and constitutional importance. Here it was that the first Norman and Plantagenet kings lived and ruled the country, and here many of them died. Here, too, all the great trials of history had been held: Wallace. the pioneer of Scottish independence; Sir Thomas More, now venerated as a saint; Guy Fawkes; King Charles I; the leaders of of the Rebellion of 1 745. In this building the House of Commons first began to exercise power as a separate entity; King Charles I tried to arrest the Members of the House who had defied him; and the great orators of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Bürke, Pitt, Gladstone, and Disraeli held their audiences spellbound. The chief and most magníficent room in the Palace, Westminster Hall, was saved: all the inadequate fire-fighting apparatus of the day was concentrated upon it. Most of the rest of the Palace was destroyed. With the tremendous self-confidence of the nineteenth century a new building was erected, more commodious, less rambling. The great Hall was retained: its magnificence, and the associations which had grown round it, made that inevitable. St Stephen's Chapel, in which the House of Commons had for three centuries met. was completely destroyed, but the Crypt Chapel underneath was retained and with it the beautiful cloisters of the Chapel - the cloakroom of the Members of the House. All the remainder of the Palace was pulled down and a new Palace. designed by Charles Barry - who had seen the blaze from his coach across the river - was erected at enormous expense. The building was for the first time given cohesion and an intelligible plan; half was given to the Lords and half to the Commons, and it stretched along the river and out into the river with a frontage of great beauty and balance. A Clock Tower was erected at one end; there had always been a clock at the end but the new clock. Big Ben, was to become the master timepiece of the nation, of the Empire. At the other end of the Palace a huge square tower of magnificent design was built, twice the height that was originally intended, yet splendidly proportioned. The entire long east and west fronts, and indeed the whole Palace, were built in the Late Gothic or Tudor style, then becoming popular. These fronts, and the whole of the interior. were profusely decorated with carvings. statues, and interior panelling and paintings, mostly designed by Barry's collaborator, Augustus Welby Pugin. The corridors were long - about two miles altogether - and the rooms - about eleven hundred of them - spacious and lofty. Because of the soft nature of the ground the Palace was built upon a slab of concrete 10 feet thick. As time went on electric lighting and modern airconditioning were introduced. When the Chamber of the House of Commons was bombed in 1940 it was rebuilt, in a very similar but more restrained and slightly more comfortable form. More rooms were built under and above the new Chamber, and inside somé of the many courtyards of the Palace. The great coal-fires which had warmed the rooms gave way to central heating in various forms. The frescoes which. with the tremendous enthusiasm of the nineteenth century. had covered many of the central rooms, began to fade and were either repaired or allowed gradually to disappear. New dining rooms were constructed with elaborate kitchens; tea rooms; then cafeterias; bars. (Many of the rooms described here are not usually open to the public.) In 1947 the great Victoria Tower was reconstructed and strengthened internally to serve as a repository of the ever-increasing output of Parliamentary records. The period when the Houses of Parliament were derided as a monstrous Gothic folly is past. We are now able to see the sheer magnificence of the building, and to appreciate the genius of the architect who assembled the whole edifice just at the one time when the country was rich enough and sufficiently confident to allow its wealth and ability to be poured into the erection of a single edifice, devoted to the essential work of a constitutional democracy. VisszaTémakörök

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Művészetek > Építészet

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Útikönyvek

- Útikönyvek > Európa > Fővárosai

- Útikönyvek > Európa > Nyugat-Európa > Városai

- Útikönyvek > Idegennyelvű útikönyvek > Angol

- Útikönyvek > Utazás, turizmus

- Útikönyvek > Természetjárás, túrák > Városnézés

- Művészetek > Építészet > Kontinensek szerint > Európa > Angol

- Művészetek > Építészet > Idegen nyelv > Angol

- Művészetek > Építészet > Műemlékek > Középületek > Államigazgatás

- Művészetek > Építészet > Műemlékek > Kastélyok

Eric Taylor

Eric Taylor műveinek az Antikvarium.hu-n kapható vagy előjegyezhető listáját itt tekintheti meg: Eric Taylor könyvek, művekMegvásárolható példányok

Nincs megvásárolható példány

A könyv összes megrendelhető példánya elfogyott. Ha kívánja, előjegyezheti a könyvet, és amint a könyv egy újabb példánya elérhető lesz, értesítjük.