1.066.456

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

VISSZA

A TETEJÉRE

JAVASLATOKÉszre-

vételek

Chronica Picta

| Kiadó: | Helikon Kiadó |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | Budapest |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Fűzött keménykötés |

| Oldalszám: | 148 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | |

| Kötetszám: | |

| Nyelv: | Latin |

| Méret: | 30 cm x 21 cm |

| ISBN: | |

| Megjegyzés: | Ez a kötet az Országos Széchényi Könyvtárban Clmae 404. jelzetlen őrzött Képes Krónika hasonmása. Színes illusztrációkkal. A kötet végén magyar, angol, német és olasz nyelvű ismertetővel. |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

Előszó

THE PICTURE CHRONICLE

The Picture Chronicle is one of the most glorious histori-cal and literary achievements of the distant Hungárián past, and a masterpiece of medieval illumination. This... Tovább

Előszó

THE PICTURE CHRONICLE

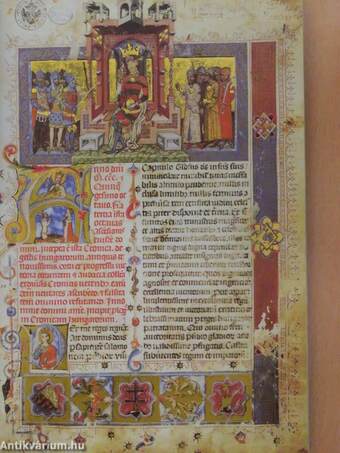

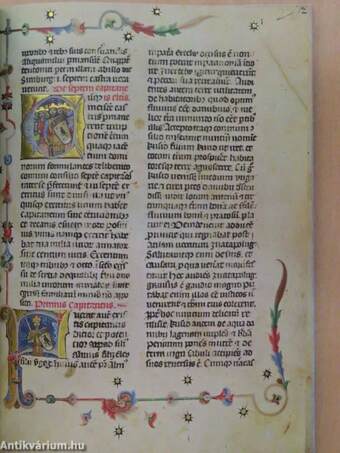

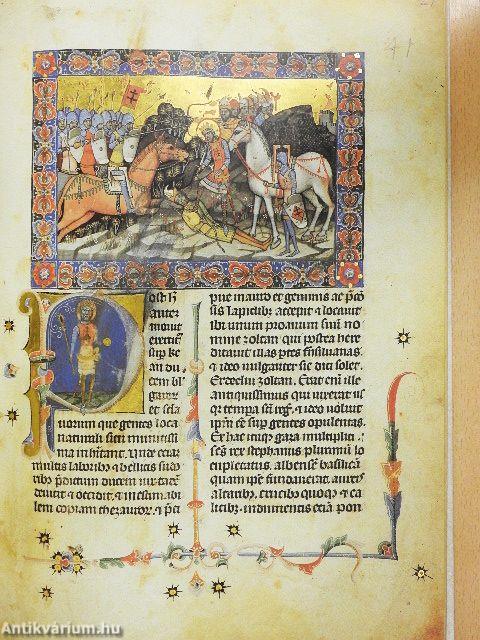

The Picture Chronicle is one of the most glorious histori-cal and literary achievements of the distant Hungárián past, and a masterpiece of medieval illumination. This compilation of chronicles dates back to the reign of King Louis I, a descendant of the House of Anjou, who, for a series of conquests including the occupation of southern Italy ruled by his Anjou kinsman, earned the epithet, "the Great". His court became the centre of early Renaissance culture and the knightly way of life. The Picture Chronicle is the result of joint effort; although it was a single person, Canon Márk Kálti, the official guardian of the monal remains, decrees, documents and gestes of the ancient kings at St. Stephen's Cathedral at Székesfehérvár who gave the chronicle its final form and structure, it is based on the works of several medieval authors. The chronicler began to write his work in 1358 and in all probability finished it before 1370.

In the prologue, the compilor of the chronicle for-mulates a theory of government, piacing the wise monarch ruling by divine right as the pillar of good government. The chief aim of his work was to prove (and support by quotations from the Bible) the proposition that a Godfearing ruler is always victorious and will make his kingdom prosper. In his opinion, the history of the Hungárián kings was a perfect illustration of this view of good government. In the chronicle itself, which begins with the Huns, the forefathers of the Magyars, he emphasizes the continuity of the succession to the throne from Attila through the Árpád dynasty and the Anjous, with the figure of St. Ladislas (c. 1040-1095), whose example the knight-king, Louis the Great followed, acting as the central figure.

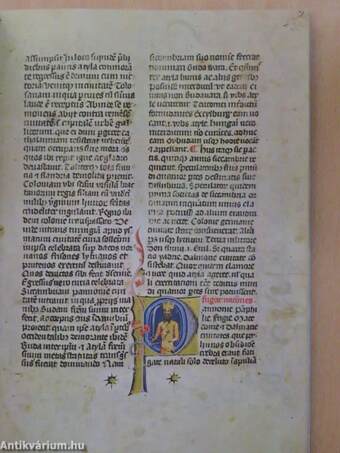

At the same time the chronicler was a genuine writer who recorded pagan legends once suppressed by the Church, thereby making them available for later poets - a whole treasure house of stories, events and figures still known to Hungárián readers today. Among these legends we can find the most beautiful version of the widely known story of the Magyar conquest, according to which Prince Árpád bought the territory of the country in exchange for a white horse from Svatopluk, Prince of Great Moravia. The Chronicle is alsó the first Hungárián codex which offers a store of information about the his-

tory of heraldry, armoury and national wear, and is one of the most important medieval documents of Hungárián historical scholarship.

The text of the Picture Chronicle represents the past as seen through the eyes of the Court, while the illumina-tions themselves reflect contemporary life and furnish us with information on architecture, costumes, and coats-of arms, among other things. He must have been equally familiar with the legends of the Hungárián saints, oral tradition, the royal family, and the world of the court. Somé scholars believe that the illuminations must be the work of the court painter of the period, Hertul's son, Miklós, others believe differently. But all the literature on the topic agrees that the illuminátor, whatever his name was, had to be a Hungárián master.

There are altogether 147 miniatures in the codex, ten large size illustrations, 29 smaller ones, four medallion-shaped pieces, 99 pictures placed inside initials, and 5 ini-tials without illustrations.

The Picture Chronicle is presendy housed in the National Széchényi Library of Budapest (inventory no. Clmae 404.) Although in the 1 jth century it was kept in Hungary, at the court of King Matthias (r. 1458-1490), from the iéth century on it belonged to the stock of the Court Library of Vienna (later cailed the Austrian National Library). Accordingly, for years the chronicle was referred to as the Viennese Chronicle. It was returned to Hungary in 1934, as the result of the cultural agreement of Venice.

On the second sheet of the Picture Chronicle, inside the encased initial "S", is the sitting figure of a man. "Is it possible," wonders György Rónay, the well-known poet and writer, "that this bearded figure, who seems to be writing something into a codex, is the author and compilor himself ? And if it is the author, can he really be Márk Kálti, Canon of Fehérvár, whose authorship is not authenticated by documents, only by a very vague oral tradition? It does not really matter. The picture is of a histórián in any case, right in the beginning of the most beautifully illustrated Hungárián codex, absorbed in his work, with a pen in his right hand and a scratching knife in his left, imbuing us with due respect for historians and historiography alike." Vissza

Témakörök

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Latin

- Művészetek > Festészet > Rajz, grafika > Illusztrációk

- Művészetek > Festészet > Idegen nyelv > Egyéb

- Történelem > Idegennyelvű > Egyéb

- Történelem > Magyarország története és személyiségei > Kalandozások, honfoglalás

- Történelem > Levelek, forráskiadványok, dokumentumok > Középkor

- Történelem > Magyarország története és személyiségei > A magyarság őstörténete

- Történelem > Magyarország története és személyiségei > Árpád-házi királyok (972-1301) > Egyéb

Kálti Márk

Kálti Márk műveinek az Antikvarium.hu-n kapható vagy előjegyezhető listáját itt tekintheti meg: Kálti Márk könyvek, művekMegvásárolható példányok

Nincs megvásárolható példány

A könyv összes megrendelhető példánya elfogyott. Ha kívánja, előjegyezheti a könyvet, és amint a könyv egy újabb példánya elérhető lesz, értesítjük.