1.067.691

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

VISSZA

A TETEJÉRE

JAVASLATOKÉszre-

vételek

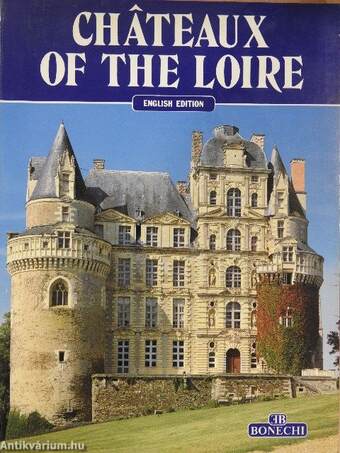

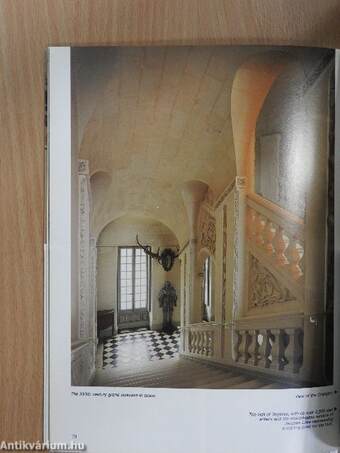

Cháteaux of the Loire

| Kiadó: | Bonechi |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | Firenze |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Fűzött papírkötés |

| Oldalszám: | 126 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | |

| Kötetszám: | |

| Nyelv: | Angol |

| Méret: | 26 cm x 20 cm |

| ISBN: | |

| Megjegyzés: | Színes fotókkal gazdagon illusztrálva. További kapcsolódó személyek a kötetben. |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

Előszó

INTR OD U CTION It seems natural to wonder why so many cháteaux are situated along a river and its tributaries on a patch of land 200 kilometers long and 100 wide. The reason may lie partly in the... TovábbElőszó

INTR OD U CTION It seems natural to wonder why so many cháteaux are situated along a river and its tributaries on a patch of land 200 kilometers long and 100 wide. The reason may lie partly in the clear blue skies and peaceful valley of a river that runs through the heart of Francé, far from troubled frontiers. On the other hand the fact that the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453), in which the idea of a nation came to the fore, was resolved here, on the river, cannot be overlooked. Each and every one of these reasons is involved but the single most valid reason is that when the members of the house of Valois returned from the wars in Italy (begun in 1494) their ideas of'residence" and "court" were no longer the same. Their castles, which up to then had been little more than rude strongholds, had lost their raison d'étre, for peace at home was now ensured and the invention of artillery had turnéd walls that seemed impregnable into fragile screens. Charles VIII, Louis XII and Francis I had assimilated the Italian model in which the measure of royal power was no longer armed might but culture, elegance, ostentation, a daily life immersed in luxury and a love of the spectacular and of being seen. Louis XII had called Laurana and Niccold Spinelli from Italy and had left the palace of the Louvre for Plessis-les-Tours. This is how it all began. Italian culture had made a breach. When Charles VIII returned from Naples in 1495, Italian artists followed in his wake. The old strongholds began to be opened up, the walls were emptied and light was ftnally allowed to enter. Only a few characteristic elements of the castlefortress still remained: the machicolations, for example, were transformed into ornamental motifs (Amboise, Chaumont, Chenonceaux, Azay-leRideau, Chambord). Openings were surrounded by friezes, and chimneys made their appearance on the roofs as real sculptural elements. Landscape gardening, with its fountains, ornamental waterworks, hedges alternated with flowerbeds, was created as an art together with the art of living. Among the artists who accompanied Charles VIII when he returned from Italy was Fra' Pacello da Marcogliano, the inventor of open spaces, who had been carried away from the Court of Naples and who had never forgottén the precise green geometrical patterns of the Sicilian orange groves. When he was in Naples Charles VIII had lived in Poggioreale which was more like a stage set for fétes and periods of relaxation than a castle. When he returned to Francé, he transformed the old fortress of Amboise into a series of halls, gardens, terraces, galleries. Charles d'Amboise, sent to Milán by order of his king, Louis XII, returned overcome by the splendid life at court and the pomp and ceremony of the Visconti court and he, too, transformed his castle of Meillant. This was when the Loire acquired a central role in the arts. The flamboyant style of the cháteaux is a new dimension in the art of the court. The nobility and the new wealth of the bourgeoisie gravitated around the Court. Bankers andftnanciers such as Berthelot at Azay-le-Rideau, Bohier at Chenonceaux, were so powerful that the kings graciously accepted loans from them. And there were alsó merchants like Jacques Coeur, whose ships and whose storehouses overflowing with silks, cotton, spices andproducts ofthe VisszaTartalom

INDEXIntroduction Page 3

Amboise " 8

Angers " 13

Azay-le-Rideau " 18

Blois " 24

Brissac " 34

Chambord " 38

Chaumont " 50

Chenonceau " 53

Cheverny " 64

Chinon " 72

Clos-Lucé " 74

Fougéres-sur-Biévre " 78

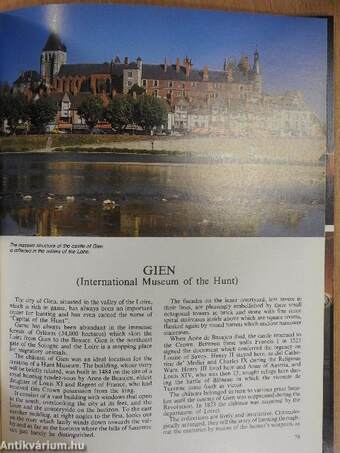

Gien " 79

Gué-Péan " 82

Langeais " 84

Le Lude " 90

Loches " 92

Montpoupon " 102

Montreuil-Bellay " 105

Montsoreau " 108

Saumur " 110

Serrant " 114

Ussé " 118

Valengay " 119

Villandry " 124

Témakörök

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Művészetek > Építészet

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Művészetek > Fotóművészet

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Útikönyvek

- Útikönyvek > Európa > Nyugat-Európa > Egyéb

- Útikönyvek > Idegennyelvű útikönyvek > Angol

- Útikönyvek > Utazás, turizmus

- Útikönyvek > Természetjárás, túrák > Egyéb

- Művészetek > Építészet > Kontinensek szerint > Európa > Egyéb

- Művészetek > Építészet > Idegen nyelv > Angol

- Művészetek > Építészet > Műemlékek > Kastélyok

- Művészetek > Fotóművészet > Albumok > Külföldi

- Művészetek > Fotóművészet > Albumok > Tematikus

- Művészetek > Fotóművészet > Idegen nyelv > Angol

- Művészetek > Fotóművészet > Témái > Művészetek

Megvásárolható példányok

Nincs megvásárolható példány

A könyv összes megrendelhető példánya elfogyott. Ha kívánja, előjegyezheti a könyvet, és amint a könyv egy újabb példánya elérhető lesz, értesítjük.