1.118.142

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

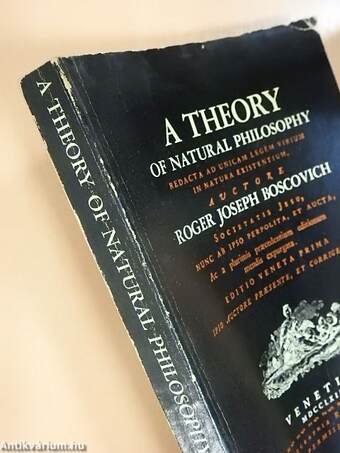

A Theory of Natural Philosophy

| Kiadó: | The M. I. T. Press |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | Cambridge |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Ragasztott papírkötés |

| Oldalszám: | 229 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | MIT |

| Kötetszám: | 49 |

| Nyelv: | Angol |

| Méret: | 23 cm x 16 cm |

| ISBN: | |

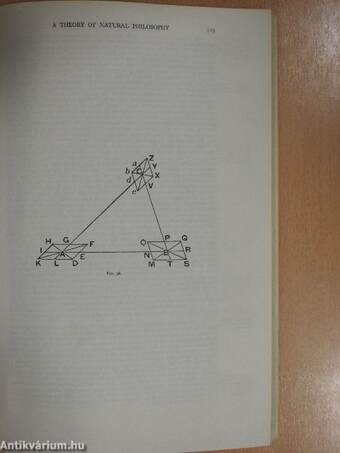

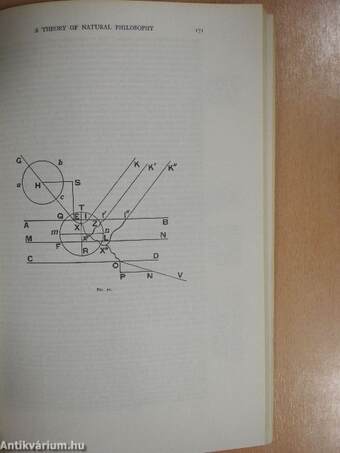

| Megjegyzés: | Néhány fekete-fehér ábrával. |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

Előszó

TovábbFülszöveg

Science

THEORY OF NATURAL PHILOSOPHY by Roger Joseph Boscovich

This translation of Theoria Philosophiae Naturalis makes accessible to the historian and philosopher of science the magnum opus of Roger Joseph Boscovich (1711-1787), one of the most far-reaching scientific thinkers of his time. In this work, Boscovich, in the first scientific generation after Newton (1642-1727), developed a speculative molecular theory of matter, and laid the groundwork for a field theory of physical action. In order to defend the principle of continuity — in particular, to solve the theoretical problems created by bodies in colHsion, which seemingly results in instantaneous changes of velocity and position — he was led to introduce an atomic theory in which matter is composed of "points of force," indivisible, without dimension or shape, but, like the atoms of Leucippus, separated by finite distances.

This assumption results in a mechanics and optics of pure geometry in the form of fields of... Tovább

Fülszöveg

Science

THEORY OF NATURAL PHILOSOPHY by Roger Joseph Boscovich

This translation of Theoria Philosophiae Naturalis makes accessible to the historian and philosopher of science the magnum opus of Roger Joseph Boscovich (1711-1787), one of the most far-reaching scientific thinkers of his time. In this work, Boscovich, in the first scientific generation after Newton (1642-1727), developed a speculative molecular theory of matter, and laid the groundwork for a field theory of physical action. In order to defend the principle of continuity — in particular, to solve the theoretical problems created by bodies in colHsion, which seemingly results in instantaneous changes of velocity and position — he was led to introduce an atomic theory in which matter is composed of "points of force," indivisible, without dimension or shape, but, like the atoms of Leucippus, separated by finite distances.

This assumption results in a mechanics and optics of pure geometry in the form of fields of force. It is known that Faraday, who developed the modern theory of fields, studied Boscovich with care. Certainly, Faraday's respect for physical continuity parallels that of Boscovich.

This theory also suggests curious — almost uncanny — intimations of general relativity and quantum physics. Boscovich treats Newton's law of gravitation as a "classical limit," a good-enough approximation where distances are large: ". . . nor, I assert, can [the law of gravitation] be deduced from astronomy, that is followed with perfect accuracy even at the distances of the planets and the comets, but one merely that is at most so very nearly correct, that the differences from the law of inverse squares is very slight." But, he argues, for phenomena on the atomic scale, Newton's "classical" law breaks down altogether, and the forces of attraction are replaced by an oscillation between attractive and repulsive forces.

In spite of his differences with Newton, Boscovich was one of the first Continental scientists to advocate the Newtonian system as an essentially true description of the universe. Of Dalmatian origin, Boscovich was a Jesuit from the age of 15 and served the Papal States and the French Court, and represented his native city of Ragusa on a diplomatic mission to England. He was elected to the Royal Society and accorded membership in the French Academy. His scientific work ranged from observations of the transit of Mercury, the determination of the figure of the Earth, and measurements of the inequalities of terrestrial gravitation, the theory of comets, and dissertations on tides, double refraction, and the cycloid.

The present text is translated from the Venetian edition of 1763, revised and enlarged by Boscovich from the Viennese edition of 1758. Vissza

Témakörök

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Természettudományok > Egyéb

- Természettudomány > Általános természettudomány > Tudomány

- Természettudomány > Általános természettudomány > Vallás

- Természettudomány > Általános természettudomány > Idegennyelvű > Angol

- Vallás > Határtudományok > Filozófia

- Filozófia > Témaköre szerint > Szakfilozófiák

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Filozófia > Témaköre szerint > Szakfilozófiák

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Vallás

- Vallás